28.2 Regulation of Gene Expression in Bacteria

As in many other areas of biochemical investigation, the study of the regulation of gene expression advanced earlier and faster in bacteria than in other experimental organisms. The examples of bacterial gene regulation presented here are chosen from among scores of well-studied systems, partly for their historical significance, but primarily because they provide a good overview of the range of regulatory mechanisms in bacteria. Many of the principles of bacterial gene regulation are also relevant to understanding gene expression in eukaryotic cells.

We begin by examining the lactose and tryptophan operons; each system has regulatory proteins, but the overall mechanisms of regulation are very different. This is followed by a short discussion of the SOS response in E. coli, illustrating how genes scattered throughout the genome can be coordinately regulated. We then describe two bacterial systems of quite different types, illustrating the diversity of gene regulatory mechanisms: regulation of ribosomal protein synthesis at the level of translation, with many of the regulatory proteins binding to RNA (rather than DNA), and regulation of the process of “phase variation” in Salmonella, which results from genetic recombination. Finally, we examine some additional examples of posttranscriptional regulation in which the RNA modulates its own function.

The lac Operon Undergoes Positive Regulation

The operator-repressor-inducer interactions described earlier for the lac operon (Fig. 28-8) provide an intuitively satisfying model for an on/off switch in the regulation of gene expression, but operon regulation is rarely so simple. A bacterium’s environment is too complex for its genes to be controlled by one signal. Other factors besides lactose, such as the availability of glucose, affect the expression of the lac genes. Glucose, metabolized directly by glycolysis, is the preferred energy source in E. coli. Other sugars can serve as the main or sole nutrient, but extra enzymatic steps are required to prepare them for entry into glycolysis, necessitating the synthesis of additional enzymes. Clearly, expressing the genes for proteins that metabolize sugars such as lactose or arabinose is wasteful when glucose is abundant.

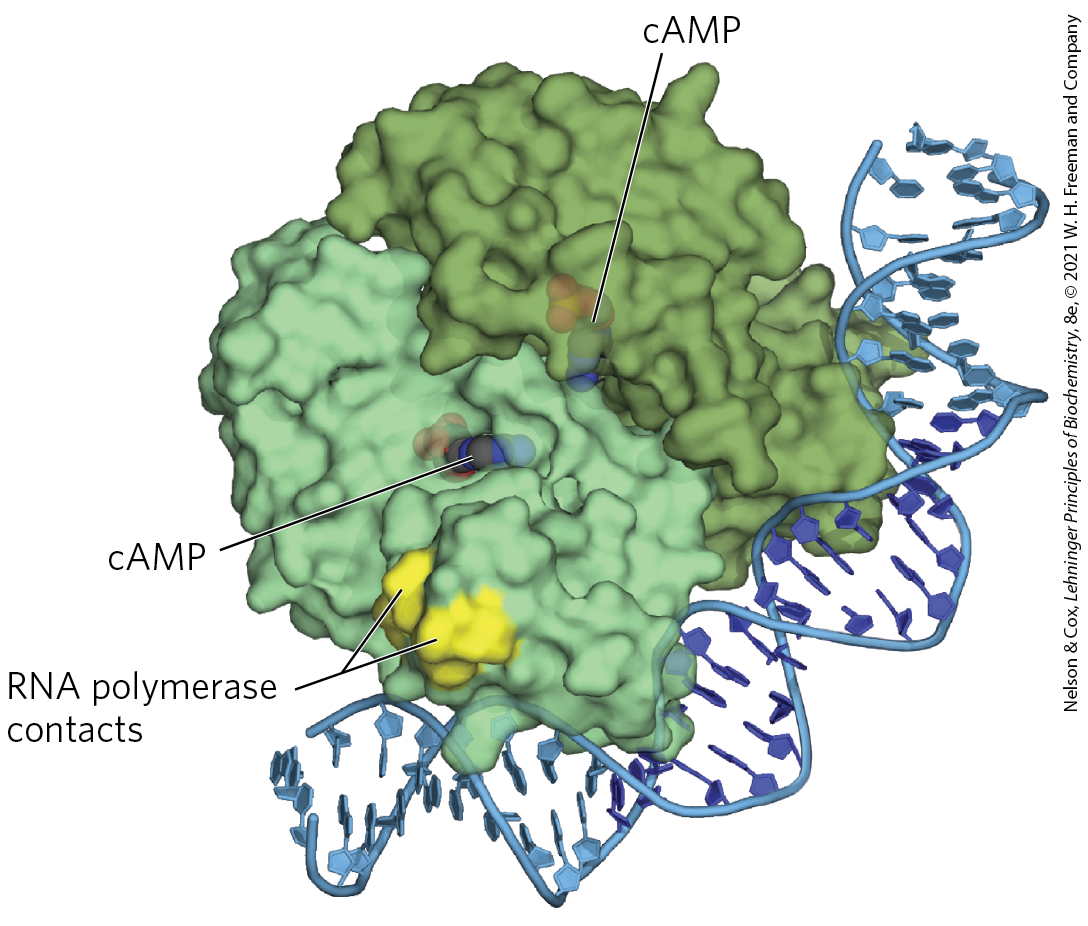

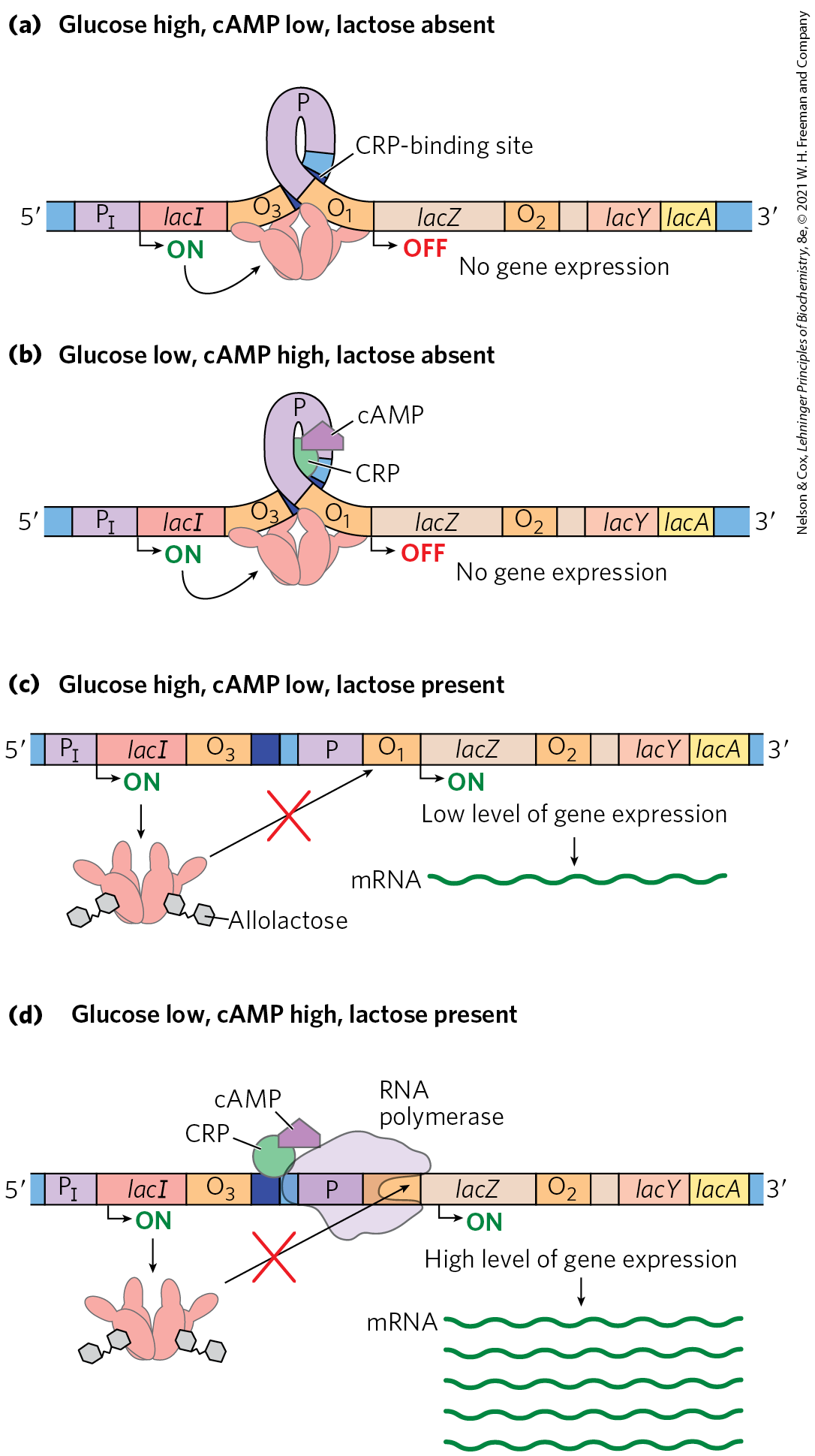

What happens to the expression of the lac operon when both glucose and lactose are present? A regulatory mechanism known as catabolite repression restricts expression of the genes required for catabolism of lactose, arabinose, and other sugars in the presence of glucose, even when these secondary sugars are also present. The effect of glucose is mediated by cAMP, as a coactivator, and an activator protein known as cAMP receptor protein, or CRP (the protein is sometimes called CAP, for catabolite gene activator protein). CRP is a homodimer (subunit ) with binding sites for DNA and cAMP. Binding is mediated by a helix-turn-helix motif in the protein’s DNA-binding domain (Fig. 28-17). When glucose is absent, CRP-cAMP binds to a site near the lac promoter (Fig. 28-18) and stimulates RNA transcription 50-fold. The wild-type lac promoter is a relatively weak promoter, diverging from the consensus shown in Figure 28-2. The open complex of RNA polymerase and the promoter (see Fig. 26-6) does not form readily unless CRP-cAMP is present and also bound (Fig. 28-18a, c). CRP-cAMP is therefore a positive regulatory element responsive to glucose levels, whereas the Lac repressor is a negative regulatory element responsive to lactose. The two act in concert. CRP-cAMP has little effect on the lac operon when the Lac repressor is blocking transcription, and dissociation of the repressor from the lac operator has little effect on transcription of the lac operon unless CRP-cAMP is present to facilitate transcription. CRP interacts directly with RNA polymerase (at the region shown in Fig. 28-17) through the polymerase’s α subunit. Thus, optimal expression of the lac operon requires dissociation of the Lac repressor (indicating that lactose is available) and the binding of CRP-cAMP (indicating that glucose is not available).

FIGURE 28-17 CRP homodimer with bound cAMP. Note the bending of the DNA around the protein. The region that interacts with RNA polymerase is labeled. [Data from PDB ID 1RUN, G. Parkinson et al., Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:837, 1996.]

FIGURE 28-18 Positive regulation of the lac operon by CRP. The binding site for CRP-cAMP is near the promoter. The combined effects of glucose and lactose availability on lac operon expression are shown. When lactose is absent, the repressor binds to the operator and prevents transcription of the lac genes. It does not matter whether glucose is (a) present or (b) absent. (c) If lactose is present, the repressor dissociates from the operator. However, if glucose is also available, low cAMP levels prevent CRP-cAMP formation and DNA binding. RNA polymerase may occasionally bind and initiate transcription, resulting in a very low level of lac genes transcription. (d) When lactose is present and glucose levels are low, cAMP levels rise. The CRP-cAMP complex forms and facilitates robust binding of RNA polymerase to the lac promoter and high levels of transcription.

The effect of glucose on CRP is mediated by the cAMP interaction (Fig. 28-18). CRP binds to DNA most avidly when cAMP concentrations are high. In the presence of glucose, the synthesis of cAMP is inhibited and efflux of cAMP from the cell is stimulated. As [cAMP] declines, CRP binding to DNA declines, thereby decreasing the expression of the lac operon.

CRP and cAMP participate in the coordinated regulation of many operons, primarily those that encode enzymes for the metabolism of secondary sugars such as lactose and arabinose. A network of operons with a common regulator is called a regulon. This arrangement, which allows coordinated shifts in cellular functions that can require the action of hundreds of genes, is a major theme in the regulated expression of dispersed networks of genes in eukaryotes. Other bacterial regulons include the heat shock gene system that responds to changes in temperature and the genes induced in E. coli as part of the SOS response to DNA damage, described later.

Many Genes for Amino Acid Biosynthetic Enzymes Are Regulated by Transcription Attenuation

The 20 common amino acids are required in large amounts for protein synthesis, and E. coli can synthesize all of them. The genes for the enzymes needed to synthesize a given amino acid are generally clustered in an operon and are expressed whenever existing supplies of that amino acid are inadequate for cellular requirements. When the amino acid is abundant, the biosynthetic enzymes are not needed and the operon is repressed.

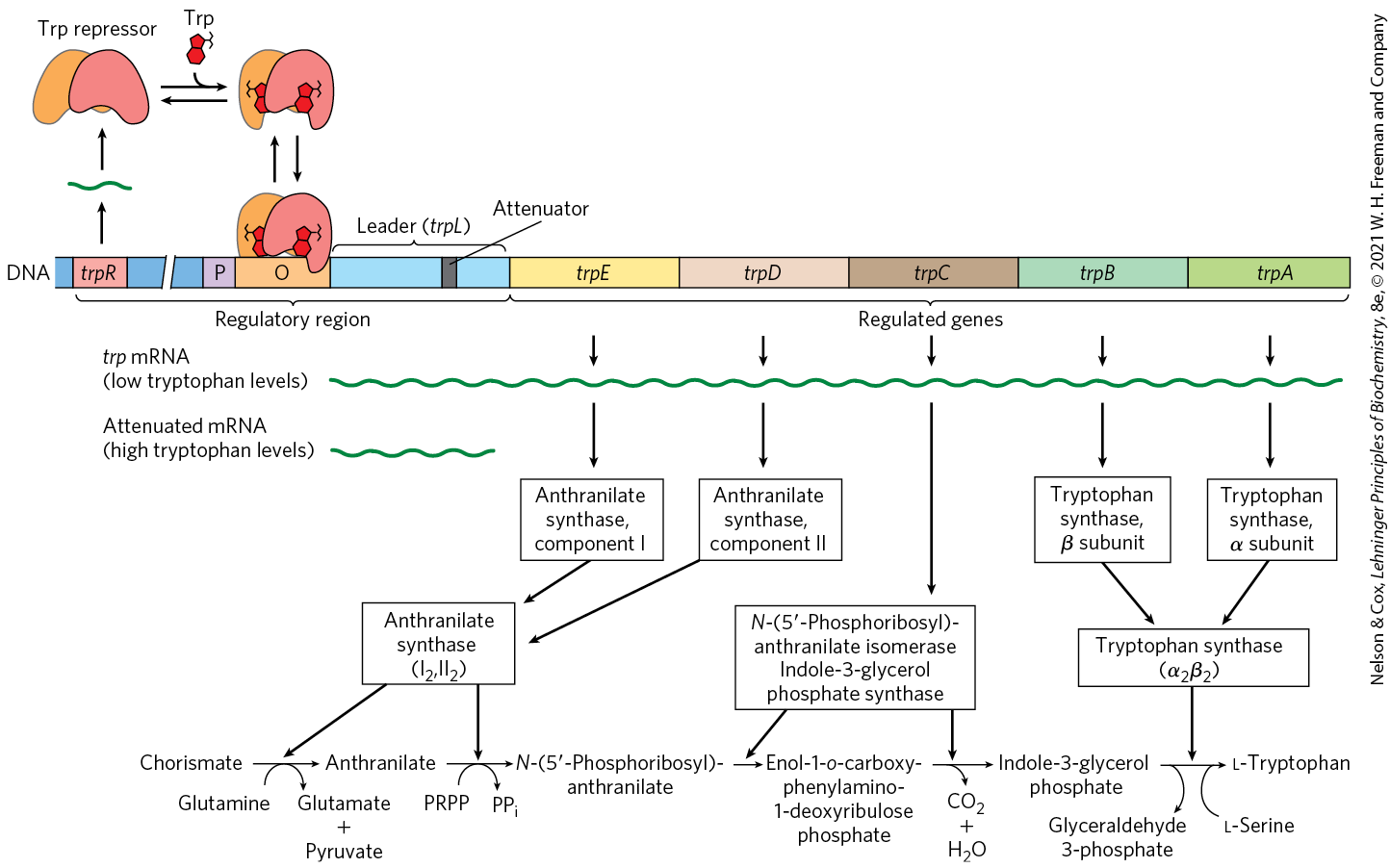

The E. coli tryptophan (trp) operon (Fig. 28-19) includes five genes for the enzymes required to convert chorismate to tryptophan (see Fig. 22-19). Note that two of the enzymes catalyze more than one step in the pathway. The mRNA from the trp operon has a half-life of only about 3 min, allowing the cell to respond rapidly to changing needs for this amino acid. The Trp repressor is a homodimer. When tryptophan is abundant, it binds to the Trp repressor, causing a conformational change that permits the repressor to bind to the trp operator and inhibit expression of the trp operon. The trp operator site overlaps the promoter, so binding of the repressor blocks binding of RNA polymerase.

FIGURE 28-19 The trp operon. This operon is regulated by two mechanisms: when tryptophan levels are high, (1) the repressor (upper left) binds to its operator and (2) transcription of trp mRNA is attenuated (see Fig. 28-20). The biosynthesis of tryptophan by the enzymes encoded in the trp operon is diagrammed at the bottom.

Once again, this simple on/off circuit mediated by a repressor is not the entire regulatory story. Different cellular concentrations of tryptophan can vary the rate of synthesis of the biosynthetic enzymes over a 700-fold range. Once repression is lifted and transcription begins, the rate of transcription is fine-tuned to cellular tryptophan requirements by a second regulatory process, called transcription attenuation, in which transcription is initiated normally but is abruptly halted before the operon genes are transcribed. The frequency with which transcription is attenuated is regulated by the availability of tryptophan and relies on the very close coupling of transcription and translation in bacteria.

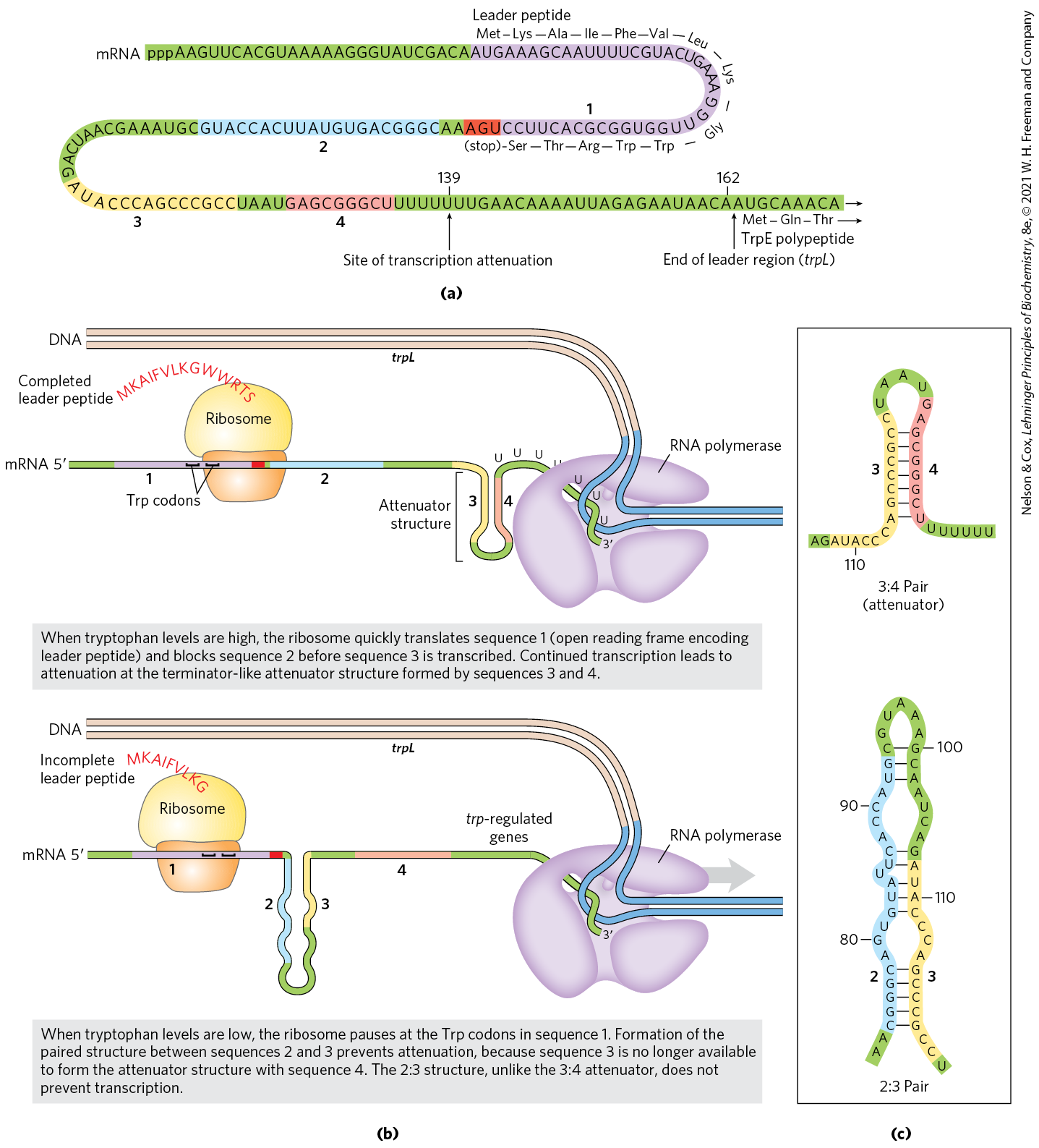

The trp operon attenuation mechanism uses signals encoded in four sequences within a 162 nucleotide leader region at the end of the mRNA, preceding the initiation codon of the first gene (Fig. 28-20a). The leader contains a region known as the attenuator, made up of sequences 3 and 4. These sequences base-pair to form a -rich stem-and-loop structure closely followed by a series of U residues. The attenuator structure acts as a transcription terminator (Fig. 28-20b; see also Fig. 26-7a). Sequence 2 is an alternative complement for sequence 3 (Fig. 28-20c). If sequences 2 and 3 base-pair, the attenuator structure cannot form and transcription continues into the trp biosynthetic genes; the loop formed by the pairing of sequences 2 and 3 does not obstruct transcription.

FIGURE 28-20 Transcriptional attenuation in the trp operon. Transcription is initiated at the beginning of the 162 nucleotide mRNA leader encoded by a DNA region called trpL (see Fig. 28-19). A regulatory mechanism determines whether transcription is attenuated at the end of the leader or continues into the structural genes. (a) The trp mRNA leader (trpL). The attenuation mechanism in the trp operon involves sequences 1 to 4 (highlighted). (b) Sequence 1 encodes a small peptide, the leader peptide, containing two Trp residues (W); it is translated immediately after transcription begins. Sequences 2 and 3 are complementary, as are sequences 3 and 4. The attenuator structure forms by the pairing of sequences 3 and 4 (top). Its structure and function are similar to those of a transcription terminator. Pairing of sequences 2 and 3 (bottom) prevents the attenuator structure from forming. Note that the leader peptide has no other cellular function. Translation of its open reading frame has a purely regulatory role that determines which complementary sequences (2 and 3, or 3 and 4) are paired. (c) Base-pairing schemes for the complementary regions of the trp mRNA leader.

Regulatory sequence 1 is crucial for a tryptophan-sensitive mechanism that determines whether sequence 3 pairs with sequence 2 (allowing transcription to continue) or with sequence 4 (attenuating transcription). Formation of the attenuator stem-and-loop structure depends on events that occur during translation of regulatory sequence 1, which encodes a leader peptide (so called because it is encoded by the leader region of the mRNA) of 14 amino acids, two of which are Trp residues. The leader peptide has no other known cellular function; its synthesis is simply an operon regulatory device. This peptide is translated immediately after it is transcribed, by a ribosome that follows closely behind RNA polymerase as transcription proceeds.

When tryptophan concentrations are high, concentrations of charged tryptophan tRNA are also high. This allows translation to proceed rapidly past the two Trp codons of sequence 1 and into sequence 2, before sequence 3 is synthesized by RNA polymerase. In this situation, sequence 2 is covered by the ribosome and unavailable for pairing to sequence 3 when sequence 3 is synthesized; the attenuator structure (sequences 3 and 4) forms and transcription halts (Fig. 28-20b, top). When tryptophan concentrations are low, however, the ribosome stalls at the two Trp codons in sequence 1, because charged is less available. Sequence 2 remains free while sequence 3 is synthesized, allowing these two sequences to base-pair and permitting transcription to proceed (Fig. 28-20b, bottom). In this way, the proportion of transcripts that are attenuated declines as tryptophan concentration declines.

Many other amino acid biosynthetic operons use a similar attenuation strategy to fine-tune biosynthetic enzymes to meet the prevailing cellular requirements. The 15 amino acid leader peptide produced by the phe operon contains seven Phe residues. The leu operon leader peptide has four contiguous Leu residues. The leader peptide for the his operon contains seven contiguous His residues. In fact, in the his operon and several others, attenuation is sufficiently sensitive to be the only regulatory mechanism.

Induction of the SOS Response Requires Destruction of Repressor Proteins

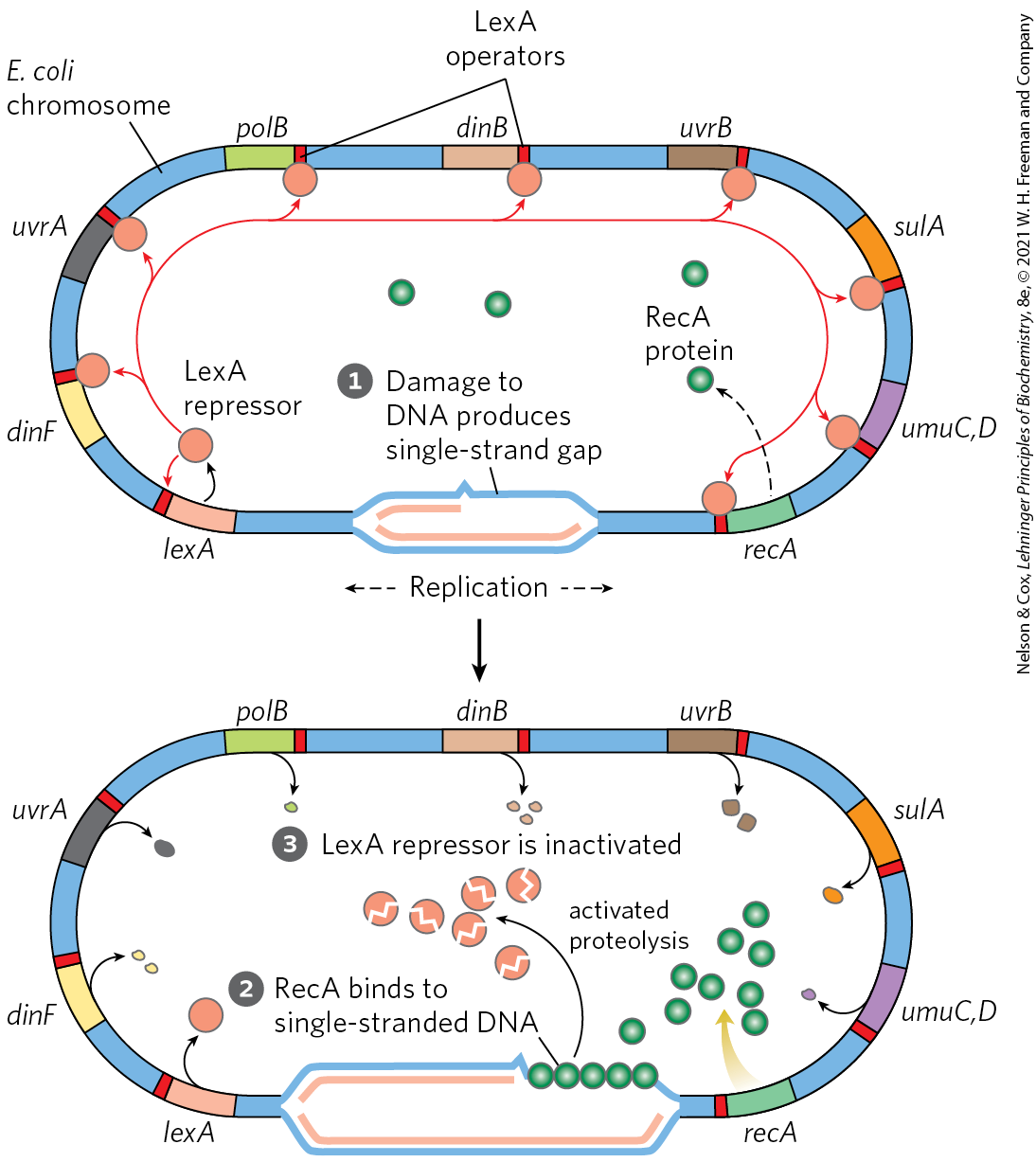

Extensive DNA damage in the bacterial chromosome triggers the induction of nearly 60 genes scattered about the chromosome. The genes involved in the coordinated inducible response, called the SOS response (p. 939), constitute the SOS regulon. Many of the induced genes are involved in DNA repair. The key regulatory proteins are the RecA protein and the LexA repressor.

The LexA repressor inhibits transcription of all the SOS genes (Fig. 28-21), and induction of the SOS response requires removal of LexA. This is not a simple dissociation from DNA in response to binding of a small molecule, as in the regulation of the lac operon described above. Instead, the LexA repressor is inactivated when it catalyzes its own cleavage at a specific Ala–Gly peptide bond, producing two roughly equal protein fragments. At physiological pH, this autocleavage reaction requires the RecA protein. RecA is not a protease in the classical sense, but its interaction with LexA enables the repressor’s self-cleavage reaction. This function of RecA is sometimes called a co-protease activity.

FIGURE 28-21 SOS response in E. coli. The LexA protein is the repressor in this system, which has an operator site near each gene. Because the recA gene is not entirely repressed by the LexA repressor, the normal cell contains about 1,000 RecA monomers. When DNA is extensively damaged (such as by UV light), DNA replication is halted and the number of single-strand gaps in the DNA increases. RecA protein binds to this damaged, single-stranded DNA, activating the protein’s co-protease activity. While bound to DNA, the RecA protein facilitates cleavage and inactivation of the LexA repressor. When the repressor is inactivated, the SOS genes, including recA, are induced; RecA levels increase 50- to 100-fold.

The RecA protein provides the functional link between the biological signal (DNA damage) and induction of the SOS genes. Heavy DNA damage leads to numerous single-strand gaps in the DNA, and only RecA that is bound to single-stranded DNA can facilitate cleavage of the LexA repressor (Fig. 28-21, bottom). Binding of RecA at the gaps eventually activates its co-protease activity, leading to cleavage of the LexA repressor and SOS induction.

During induction of the SOS response in a severely damaged cell, RecA also promotes the autocatalytic cleavage of, and thus inactivates, the repressors that otherwise allow propagation of certain viruses in a dormant lysogenic state within the bacterial host. This provides a remarkable illustration of evolutionary adaptation. These repressors, like LexA, undergo self-cleavage at a specific Ala–Gly peptide bond, so induction of the SOS response permits replication of the virus and lysis of the cell, releasing new viral particles. Thus, the bacteriophage can make a hasty exit from a compromised bacterial host cell.

The destruction of the LexA repressor proteins as part of the response means that LexA must be resynthesized in order to reestablish gene control when the DNA damage is no longer present. The considerable amount of ATP and GTP needed for protein synthesis to maintain SOS regulon repression provides one example of the energetic cost of regulation.

Synthesis of Ribosomal Proteins Is Coordinated with rRNA Synthesis

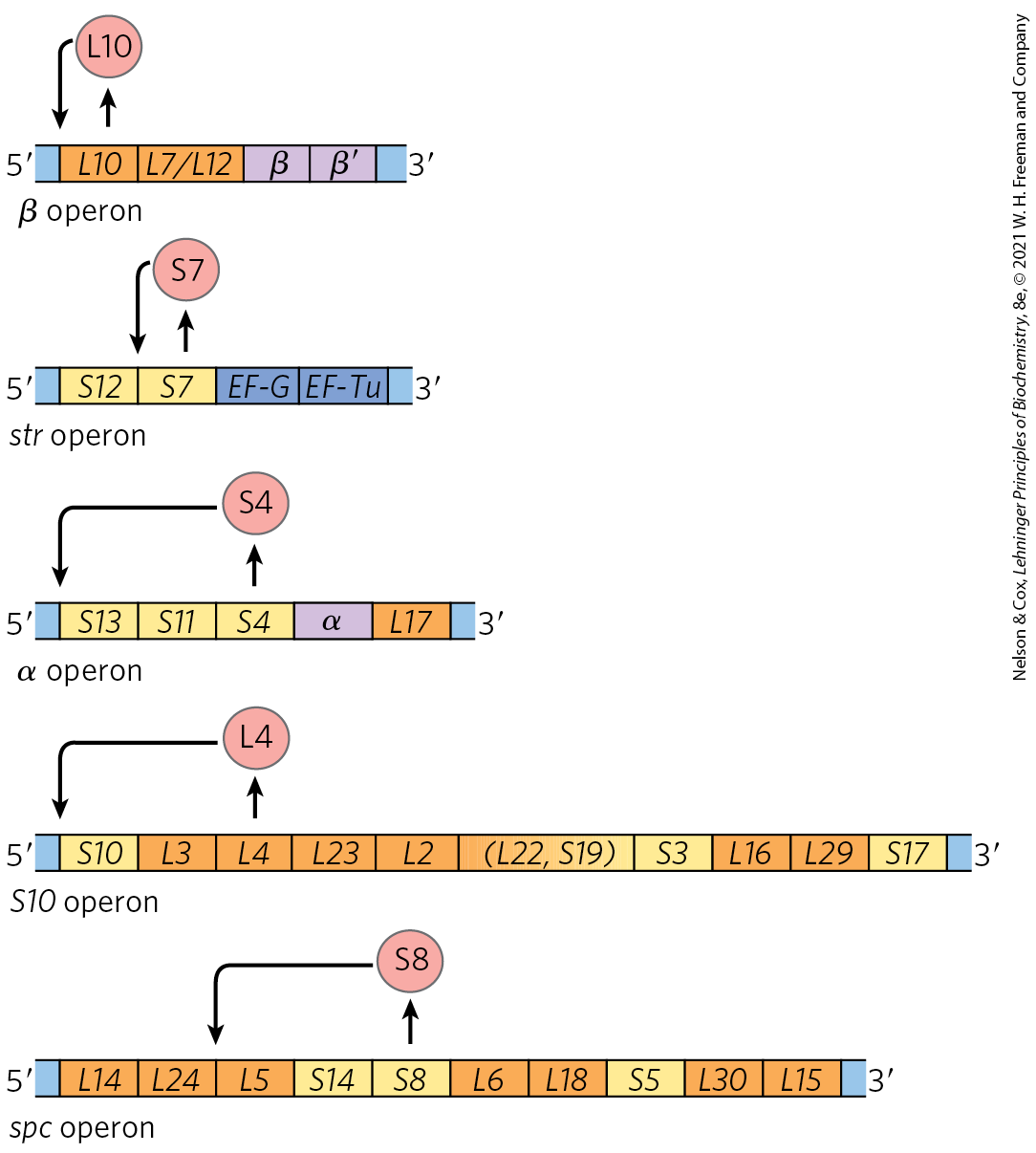

In bacteria, an increased cellular demand for protein synthesis is met by increasing the number of ribosomes rather than altering the activity of individual ribosomes. In general, the number of ribosomes increases as the cellular growth rate increases. At high growth rates, ribosomes make up approximately 45% of the cell’s dry weight. The proportion of cellular resources devoted to making ribosomes is so large, and the function of ribosomes so important, that cells must coordinate the synthesis of the ribosomal components: the ribosomal proteins (r-proteins) and RNAs (rRNAs). This regulation is distinct from the mechanisms described so far: it occurs largely at the level of translation.

The 52 genes that encode the r-proteins are distributed across at least 20 operons, each with 1 to 11 genes. Some of these operons also contain the genes for the subunits of DNA primase, RNA polymerase, and protein synthesis elongation factors — reflecting the close coupling of replication, transcription, and protein synthesis during bacterial cell growth.

The r-protein operons are regulated primarily through a translational feedback mechanism. One r-protein encoded by each operon also functions as a translational repressor, which binds to the mRNA transcribed from that operon and blocks translation of all the genes the messenger encodes (Fig. 28-22). In general, the r-protein that plays the role of repressor also binds directly to an rRNA. Each translational repressor r-protein binds with higher affinity to the appropriate rRNA than to its mRNA, so the mRNA is bound and translation repressed only when the level of the r-protein exceeds that of the rRNA. This ensures that translation of the mRNAs encoding r-proteins is repressed only when synthesis of these r-proteins exceeds that needed to make functional ribosomes. In this way, the rate of r-protein synthesis is kept in balance with rRNA availability.

FIGURE 28-22 Translational feedback in some ribosomal protein operons. The r-proteins that act as translational repressors are shown (red circles). Each translational repressor blocks the translation of all genes in that operon by binding to the indicated site on the mRNA. The operons include the genes that encode the α, β, and subunits of RNA polymerase and the elongation factors EF-G and EF-Tu (labeled). The r-proteins of the large (50S) ribosomal subunit are designated L1 to L34; those of the small (30S) subunit are designated S1 to S21.

The mRNA-binding site for the translational repressor is near the translational start site of one of the genes in the operon, often but not always the first gene (Fig. 28-22). In other operons this would affect only that one gene, because in bacterial polycistronic mRNAs, most genes have independent translation signals. In the r-protein operons, however, the translation of one gene depends on the translation of all the others. The translation of multiple genes seems to be blocked by folding of the mRNA into an elaborate three-dimensional structure that is stabilized both by internal base pairing and by binding of the translational repressor protein. When the translational repressor is absent, ribosome binding and translation of one or more of the genes disrupts the folded structure of the mRNA and allows all the genes to be translated.

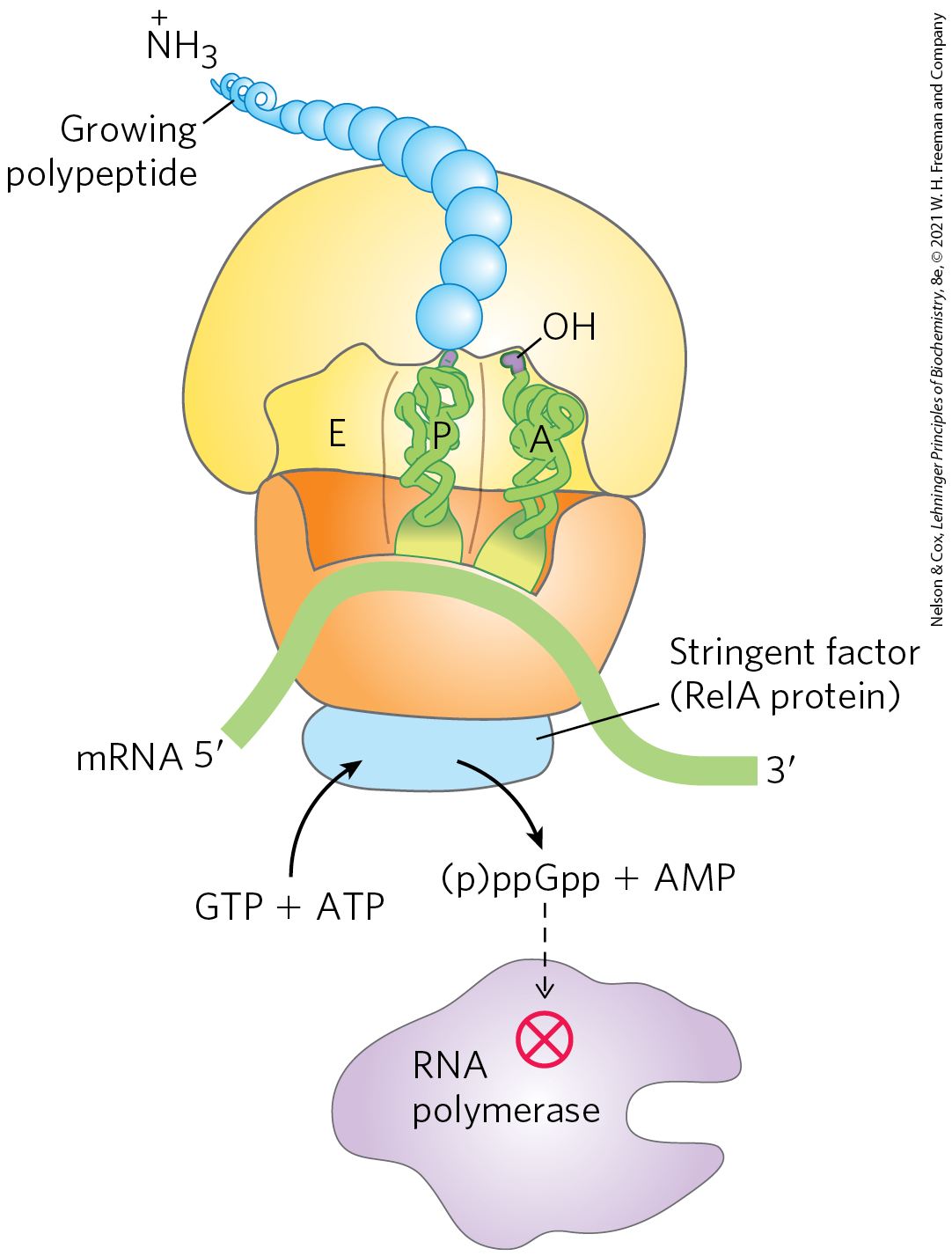

Because the synthesis of r-proteins is coordinated with the availability of rRNA, the regulation of ribosome production reflects the regulation of rRNA synthesis. In E. coli, rRNA synthesis from the seven rRNA operons responds to cellular growth rate and to changes in the availability of crucial nutrients, particularly amino acids. The regulation coordinated with amino acid concentrations is known as the stringent response (Fig. 28-23). When amino acid concentrations are low, rRNA synthesis is halted. Amino acid starvation leads to the binding of uncharged tRNAs to the ribosomal A site; this triggers a sequence of events that begins with the binding of an enzyme called stringent factor (RelA protein) to the ribosome. When bound to the ribosome, stringent factor catalyzes formation of the unusual nucleotide guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp); it adds pyrophosphate to the position of GTP, in the reaction

Then a phosphohydrolase cleaves off one phosphate to convert some pppGpp to ppGpp. The abrupt rise in pppGpp and ppGpp levels in response to amino acid starvation results in a great reduction in rRNA synthesis, mediated at least in part by the binding of ppGpp to RNA polymerase.

FIGURE 28-23 Stringent response in E. coli. This response to amino acid starvation is triggered by binding of an uncharged tRNA in the ribosomal A site. A protein called stringent factor binds to the ribosome and catalyzes the synthesis of pppGpp, which is converted by a phosphohydrolase to ppGpp. The signal ppGpp reduces transcription of some genes and increases transcription of others, in part by binding to the β subunit of RNA polymerase and altering the enzyme’s promoter specificity. Synthesis of rRNA is reduced when ppGpp levels increase.

The nucleotides pppGpp and ppGpp, along with cAMP, belong to a class of modified nucleotides that act as cellular second messengers. In E. coli, these two nucleotides serve as starvation signals; they cause large changes in cellular metabolism by increasing or decreasing the transcription of hundreds of genes. In eukaryotic cells, similar nucleotide second messengers also have multiple regulatory functions. The coordination of cellular metabolism with cell growth is highly complex, and further regulatory mechanisms undoubtedly remain to be discovered.

The Function of Some mRNAs Is Regulated by Small RNAs in Cis or in Trans

As described throughout this chapter, proteins play an important and well-documented role in regulating gene expression. But RNA also has a crucial role — one that is becoming increasingly recognized as more examples of regulatory RNAs are discovered. Once an mRNA is synthesized, its functions can be controlled by RNA-binding proteins, as seen for the r-protein operons just described, or by an RNA. A separate RNA molecule may bind to the mRNA “in trans” and affect its activity. Alternatively, a portion of the mRNA itself may regulate its own function. When part of a molecule affects the function of another part of the same molecule, it is said to act “in cis.”

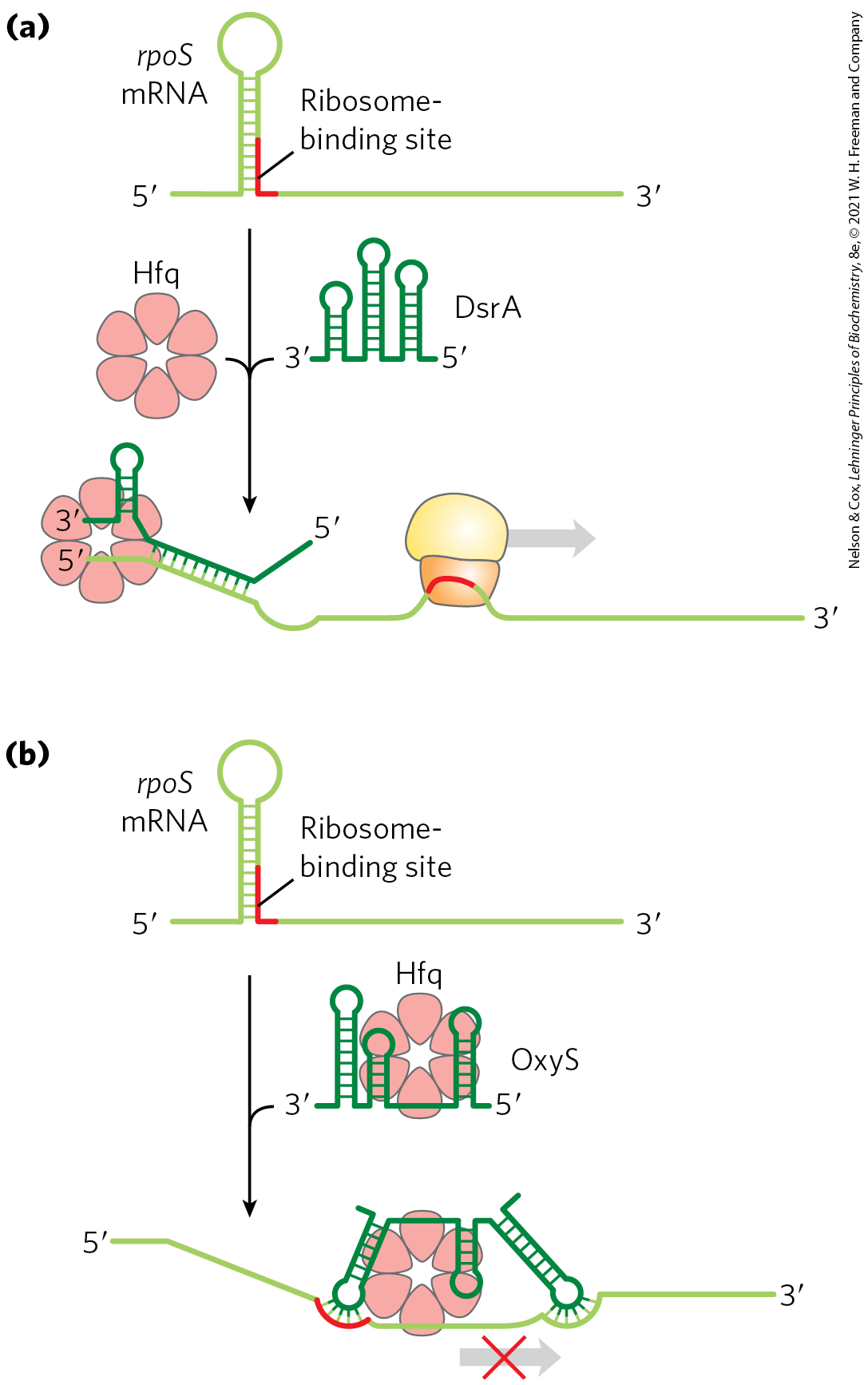

A well-characterized example of RNA regulation in trans is regulation of the mRNA of the gene rpoS (RNA polymerase sigma factor), which encodes (formerly known as ), one of seven E. coli sigma factors. The cell uses this specificity factor in certain stress situations, such as when it enters the stationary phase (a state of no growth, necessitated by lack of nutrients) and is needed to transcribe large numbers of stress response genes. The mRNA is present at low levels under most conditions but is not translated, because a large hairpin structure upstream of the coding region inhibits ribosome binding (Fig. 28-24). Under certain stress conditions, one or both of two small ncRNAs, DsrA (downstream region A) and RprA (rpoS regulator RNA A), are induced. Both can pair with one strand of the hairpin in the mRNA, disrupting the hairpin and thus allowing translation of rpoS.

FIGURE 28-24 Regulation of bacterial mRNA function in trans by sRNAs. Several sRNAs (small RNAs) — DsrA, RprA, and OxyS — participate in regulation of the rpoS gene. All require the protein Hfq, an RNA chaperone that facilitates RNA-RNA pairing. Hfq has a toroid structure, with a pore in the center. (a) DsrA promotes translation by pairing with one strand of a stem-loop structure that otherwise blocks the ribosome-binding site. RprA (not shown) acts in a similar way. (b) OxyS blocks translation by pairing with the ribosome-binding site. [Information from M. Szymański and J. Barciszewski, Genome Biol. 3:reviews0005.1, 2002.]

Another small RNA, OxyS (oxidative stress gene S), is induced under conditions of oxidative stress and inhibits the translation of rpoS, probably by pairing with and blocking the ribosome-binding site on the mRNA. OxyS is expressed as part of a system that responds to a different type of stress (oxidative damage) than does the rpoS RNA, and its task is to prevent expression of unneeded repair pathways. DsrA, RprA, and OxyS are all relatively small bacterial RNA molecules (less than 300 nucleotides), designated sRNAs (s for small; there are, of course, other “small” RNAs with other designations in eukaryotes). All sRNAs require for their function a protein called Hfq, an RNA chaperone that facilitates RNA-RNA pairing. The known bacterial genes regulated in this way are few in number, just a few dozen in a typical bacterial species. However, these examples provide good model systems for understanding patterns present in the more complex and numerous examples of RNA-mediated regulation in eukaryotes.

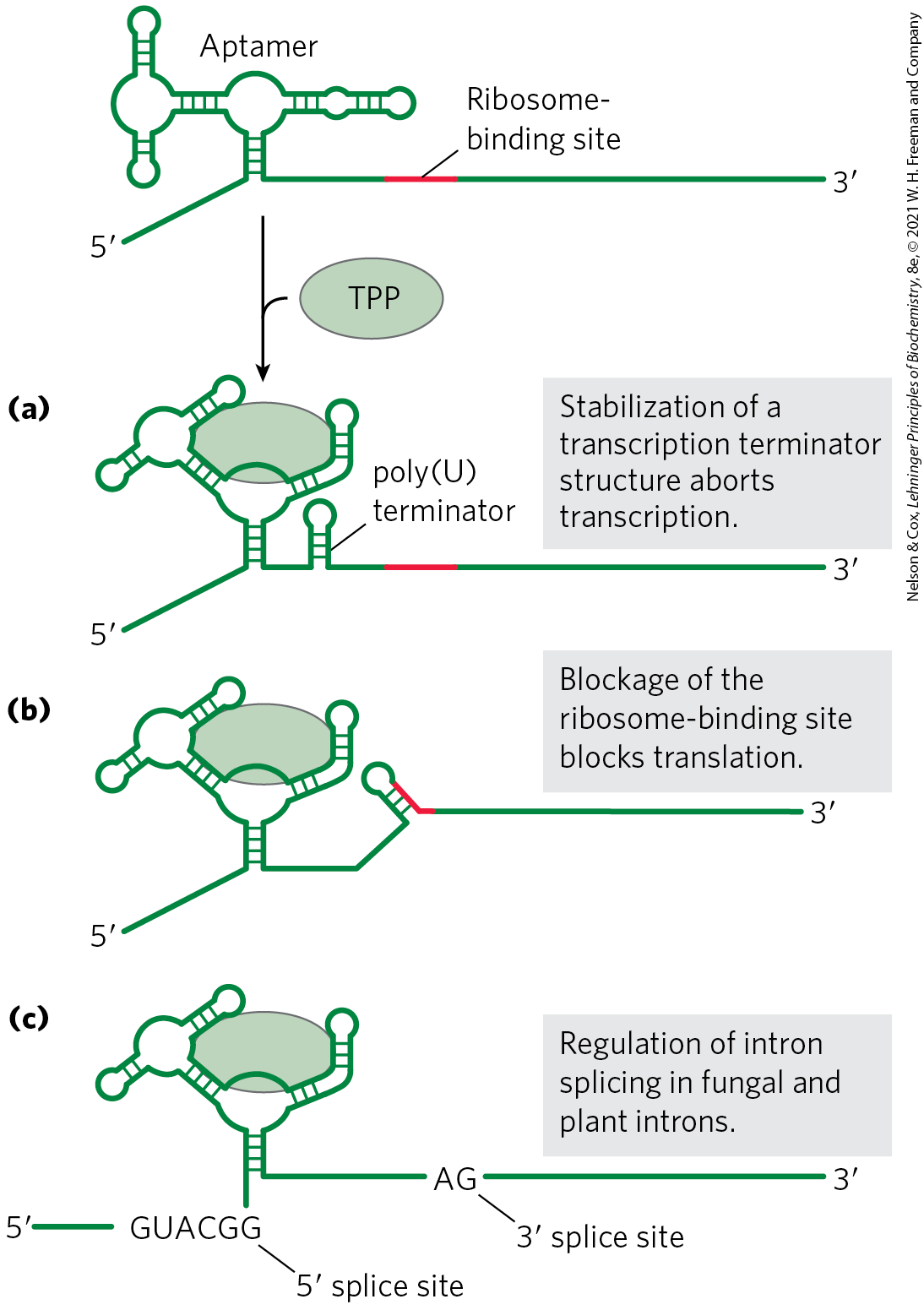

Regulation in cis involves a class of RNA structures known as riboswitches. As described in Box 26-4, aptamers are RNA molecules, generated in vitro, that are capable of specific binding to a particular ligand. As one might expect, such ligand-binding RNA domains are also present in nature — in riboswitches — in a significant number of bacterial mRNAs (and even in some eukaryotic mRNAs). These natural aptamers are structured domains found in untranslated regions at the ends of certain bacterial mRNAs. Some riboswitches also regulate the transcription of certain noncoding RNAs. Binding of an mRNA’s riboswitch to its appropriate ligand results in a conformational change in the mRNA, and transcription is inhibited by stabilization of a premature transcription termination structure, or translation is inhibited (in cis) by occlusion of the ribosome-binding site (Fig. 28-25). In most cases, the riboswitch acts in a kind of feedback loop. Most genes regulated in this way are involved in the synthesis or transport of the ligand that is bound by the riboswitch; thus, when the ligand is present in high concentrations, the riboswitch inhibits expression of the genes needed to replenish this ligand.

FIGURE 28-25 Regulation of bacterial mRNA function in cis by riboswitches. The known modes of action are illustrated by several different riboswitches, based on a widespread natural aptamer that binds thiamine pyrophosphate. TPP binding to the aptamer leads to a conformational change that produces the varied results illustrated in (a), (b), and (c) in several different systems in which the aptamer is utilized. [Information from W. C. Winkler and R. R. Breaker, Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59:487, 2005.]

Each riboswitch binds only one ligand. Distinct riboswitches have been detected that respond to more than a dozen different ligands, including thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP, ), cobalamin , flavin mononucleotide, lysine, S-adenosylmethionine (adoMet), purines, N-acetylglucosamine 6-phosphate, glycine, and some metal cations such as . It is likely that many more remain to be discovered. The riboswitch that responds to TPP seems to be the most widespread; it is found in many bacteria, fungi, and some plants. The bacterial TPP riboswitch inhibits translation in some species and induces premature transcription termination in others (Fig. 28-25). The eukaryotic TPP riboswitch is found in the introns of certain genes and modulates the alternative splicing of those genes. It is not yet clear how common riboswitches are. However, estimates suggest that more than 4% of the genes of Bacillus subtilis are regulated by riboswitches.

Most of the riboswitches described to date, including the one that responds to adoMet, have been found only in bacteria. A drug that bound to and activated the adoMet riboswitch would shut down the genes encoding the enzymes that synthesize and transport adoMet, effectively starving the bacterial cells of this essential cofactor. Drugs of this type are being sought for use as a new class of antibiotics.

The pace of discovery of functional RNAs shows no signs of abating and continues to bolster the hypothesis that RNA played a special role in the evolution of life (Chapter 26). The sRNAs and riboswitches, like ribozymes and ribosomes, may be vestiges of an RNA world obscured by time but persisting as a rich array of biological devices still functioning in the biosphere. The laboratory selection of aptamers and ribozymes with novel ligand-binding and enzymatic functions tells us that the RNA-based activities necessary for a viable RNA world are possible. Discovery of many of the same RNA functions in living organisms tells us that key components for RNA-based metabolism do exist. For example, the natural aptamers of riboswitches may be derived from RNAs that, billions of years ago, bound to cofactors needed to promote the enzymatic processes required for metabolism in the RNA world.

Some Genes Are Regulated by Genetic Recombination

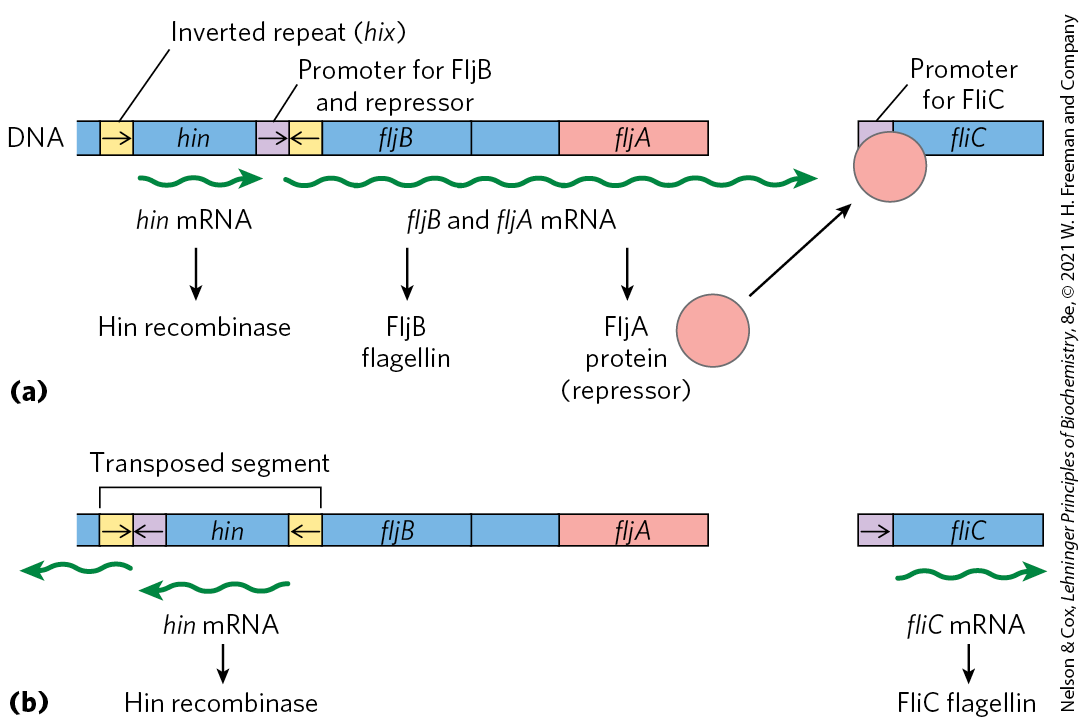

We turn now to another mode of bacterial gene regulation, at the level of DNA rearrangement — recombination. Salmonella typhimurium, which inhabits the mammalian intestine, moves by rotating the flagella on its cell surface (Fig. 28-26). The many copies of the protein flagellin that make up the flagella are prominent targets of mammalian immune systems. But Salmonella cells have a mechanism that evades the immune response: they switch between two distinct flagellin proteins (FljB and FliC) roughly once every 1,000 generations, using a process called phase variation.

FIGURE 28-26 Salmonella typhimurium. The appendages emanating from the cell are flagella.

The switch is accomplished by periodic inversion of a segment of DNA containing the promoter for a flagellin gene. The inversion is a site-specific recombination reaction (see Fig. 25-37) mediated by the Hin recombinase at specific 14 bp sequences (hix sequences) at each end of the DNA segment. When the DNA segment is in one orientation, the gene for FljB flagellin and the gene encoding a repressor, FljA, are expressed (Fig. 28-27a); the repressor shuts down expression of the gene for FliC flagellin. When the DNA segment is inverted (Fig. 28-27b), the fljA and fljB genes are no longer transcribed, and the fliC gene is induced as the repressor becomes depleted. The Hin recombinase, encoded by the hin gene in the DNA segment that undergoes inversion, is expressed when the DNA segment is in either orientation, so the cell can always switch from one state to the other.

FIGURE 28-27 Regulation of flagellin genes in Salmonella: phase variation. The products of genes fliC and fljB are different flagellins. The hin gene encodes the recombinase that catalyzes inversion of the DNA segment containing the fljB promoter and the hin gene. The recombination sites (inverted repeats) are called hix. (a) In one orientation, fljB is expressed along with a repressor protein (product of the fljA gene) that represses transcription of the fliC gene. (b) In the opposite orientation, only the fliC gene is expressed; the fljA and fljB genes cannot be transcribed. The interconversion between these two states, known as phase variation, also requires two other nonspecific DNA-binding proteins (not shown), HU and FIS.

This type of regulatory mechanism has the advantage of being absolute: gene expression is impossible when the gene is physically separated from its promoter (note the position of the fljB promoter in Fig. 28-27b). An absolute on/off switch may be important in this system (even though it affects only one of the two flagellin genes) because a flagellum with just one copy of the wrong flagellin might be vulnerable to host antibodies against that protein. The Salmonella system is by no means unique. Similar regulatory systems occur in some other bacteria and in some bacteriophages, and recombination systems with similar functions have been found in eukaryotes (Table 28-1). Gene regulation by DNA rearrangements that move genes and/or promoters is particularly common in pathogens that benefit by changing their host range or by changing their surface proteins, thereby staying ahead of host immune systems.

System |

Recombinase/recombination site |

Type of recombination |

Function |

|---|---|---|---|

Phase variation (Salmonella) |

Hin/hix |

Site-specific |

Alternative expression of two flagellin genes allows evasion of host immune response. |

Host range (bacteriophage μ) |

Gin/gix |

Site-specific |

Alternative expression of two sets of tail fiber genes affects host range. |

Mating-type switch (yeast) |

HO endonuclease, RAD52 protein, other proteins/MAT |

Nonreciprocal gene conversiona |

Alternative expression of two mating types of yeast, a and α, creates cells of different mating types that can mate and undergo meiosis. |

Antigenic variation (trypanosomes)b |

Varies |

Nonreciprocal gene conversiona |

Successive expression of different genes encoding the variable surface glycoproteins (VSGs) allows evasion of host immune response. |

a In nonreciprocal gene conversion (a class of recombination events not discussed in Chapter 25), genetic information is moved from one part of the genome (where it is silent) to another (where it is expressed). The reaction is similar to replicative transposition (see Fig. 25-41). b Trypanosomes cause African sleeping sickness and other diseases (see Box 6-1). The outer surface of a trypanosome is made up of multiple copies of a single VSG, the major surface antigen. A cell can change surface antigens to more than 100 different forms, precluding an effective defense by the host immune system. |

|||

SUMMARY 28.2 Regulation of Gene Expression in Bacteria

- In addition to repression by the Lac repressor, the E. coli lac operon undergoes positive regulation by the cAMP receptor protein (CRP). When [glucose] is low, [cAMP] is high and CRP-cAMP binds to a specific site on the DNA, stimulating transcription of the lac operon and production of lactose-metabolizing enzymes. The presence of glucose depresses [cAMP], decreasing expression of lac and other genes involved in metabolism of secondary sugars. A group of coordinately regulated operons is referred to as a regulon.

- Operons that produce the enzymes of amino acid synthesis have a regulatory circuit called attenuation, which uses a transcription termination site, called the attenuator, in the mRNA. Formation of the attenuator is modulated by a mechanism that couples transcription and translation while responding to small changes in amino acid concentration.

- In the SOS system, multiple unlinked genes repressed by a single repressor are induced simultaneously when DNA damage triggers RecA protein–facilitated autocatalytic proteolysis of the repressor.

- In the synthesis of ribosomal proteins, one protein in each r-protein operon acts as a translational repressor. The mRNA is bound by the repressor, and translation is blocked only when the r-protein is present in excess of available rRNA.

- Posttranscriptional regulation of some mRNAs is mediated by sRNAs that act in trans or by riboswitches, part of the mRNA structure itself, that act in cis.

- Some genes are regulated by genetic recombination processes that move promoters relative to the genes being regulated. Regulation can also take place at the level of translation.

Once repression is lifted and transcription begins, the rate of transcription is fine-tuned to cellular tryptophan requirements by a second regulatory process, called transcription attenuation, in which transcription is initiated normally but is abruptly halted before the operon genes are transcribed. The frequency with which transcription is attenuated is regulated by the availability of tryptophan and relies on the very close coupling of transcription and translation in bacteria.

Once repression is lifted and transcription begins, the rate of transcription is fine-tuned to cellular tryptophan requirements by a second regulatory process, called transcription attenuation, in which transcription is initiated normally but is abruptly halted before the operon genes are transcribed. The frequency with which transcription is attenuated is regulated by the availability of tryptophan and relies on the very close coupling of transcription and translation in bacteria. The genes involved in the coordinated inducible response, called the SOS response (

The genes involved in the coordinated inducible response, called the SOS response ( When DNA is extensively damaged (such as by UV light), DNA replication is halted and the number of single-strand gaps in the DNA increases.

When DNA is extensively damaged (such as by UV light), DNA replication is halted and the number of single-strand gaps in the DNA increases.  RecA protein binds to this damaged, single-stranded DNA, activating the protein’s co-protease activity.

RecA protein binds to this damaged, single-stranded DNA, activating the protein’s co-protease activity.  While bound to DNA, the RecA protein facilitates cleavage and inactivation of the LexA repressor. When the repressor is inactivated, the SOS genes, including recA, are induced; RecA levels increase 50- to 100-fold.

While bound to DNA, the RecA protein facilitates cleavage and inactivation of the LexA repressor. When the repressor is inactivated, the SOS genes, including recA, are induced; RecA levels increase 50- to 100-fold. The considerable amount of ATP and GTP needed for protein synthesis to maintain SOS regulon repression provides one example of the energetic cost of regulation.

The considerable amount of ATP and GTP needed for protein synthesis to maintain SOS regulon repression provides one example of the energetic cost of regulation. Under certain stress conditions, one or both of two small ncRNAs, DsrA (downstream region A) and RprA (rpoS regulator RNA A), are induced. Both can pair with one strand of the hairpin in the mRNA, disrupting the hairpin and thus allowing translation of rpoS.

Under certain stress conditions, one or both of two small ncRNAs, DsrA (downstream region A) and RprA (rpoS regulator RNA A), are induced. Both can pair with one strand of the hairpin in the mRNA, disrupting the hairpin and thus allowing translation of rpoS. Most of the riboswitches described to date, including the one that responds to adoMet, have been found only in bacteria. A drug that bound to and activated the adoMet riboswitch would shut down the genes encoding the enzymes that synthesize and transport adoMet, effectively starving the bacterial cells of this essential cofactor. Drugs of this type are being sought for use as a new class of antibiotics.

Most of the riboswitches described to date, including the one that responds to adoMet, have been found only in bacteria. A drug that bound to and activated the adoMet riboswitch would shut down the genes encoding the enzymes that synthesize and transport adoMet, effectively starving the bacterial cells of this essential cofactor. Drugs of this type are being sought for use as a new class of antibiotics.

In addition to repression by the Lac repressor, the E. coli lac operon undergoes positive regulation by the cAMP receptor protein (CRP). When [glucose] is low, [cAMP] is high and CRP-cAMP binds to a specific site on the DNA, stimulating transcription of the lac operon and production of lactose-metabolizing enzymes. The presence of glucose depresses [cAMP], decreasing expression of lac and other genes involved in metabolism of secondary sugars. A group of coordinately regulated operons is referred to as a regulon.

In addition to repression by the Lac repressor, the E. coli lac operon undergoes positive regulation by the cAMP receptor protein (CRP). When [glucose] is low, [cAMP] is high and CRP-cAMP binds to a specific site on the DNA, stimulating transcription of the lac operon and production of lactose-metabolizing enzymes. The presence of glucose depresses [cAMP], decreasing expression of lac and other genes involved in metabolism of secondary sugars. A group of coordinately regulated operons is referred to as a regulon.