13.4 Biological Oxidation-Reduction Reactions

The transfer of phosphoryl groups is a central feature of metabolism. Equally important is another kind of transfer: electron transfer in oxidation-reduction reactions, sometimes referred to as redox reactions. These reactions involve the loss of electrons by one chemical species, which is thereby oxidized, and the gain of electrons by another, which is reduced. The flow of electrons in oxidation-reduction reactions is responsible, directly or indirectly, for all work done by living organisms. In nonphotosynthetic organisms, the sources of electrons are reduced compounds (foods); in photosynthetic organisms, the initial electron donor is a chemical species excited by the absorption of light. The path of electron flow in metabolism is complex. Electrons move from various metabolic intermediates to specialized electron carriers in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. The carriers, in turn, donate electrons to acceptors with higher electron affinities, with the release of energy. Cells possess a variety of molecular energy transducers, which convert the energy of electron flow into useful work.

We begin by discussing how work can be accomplished by an electromotive force (emf), then consider the theoretical and experimental basis for measuring energy changes in oxidation reactions in terms of emf and the relationship between this force, expressed in volts, and the free-energy change, expressed in joules. We also describe the structures and oxidation-reduction chemistry of the most common of the specialized electron carriers, which you will encounter repeatedly in later chapters.

The Flow of Electrons Can Do Biological Work

Every time we use a motor, an electric light or heater, or a spark to ignite gasoline in a car engine, we use the flow of electrons to accomplish work. In the circuit that powers a motor, the source of electrons can be a battery containing two chemical species that differ in affinity for electrons. Electrical wires provide a pathway for electron flow from the chemical species at one pole of the battery, through the motor, to the chemical species at the other pole of the battery. Because the two chemical species differ in their affinity for electrons, electrons flow spontaneously through the circuit, driven by a force proportional to the difference in electron affinity, the electromotive force, emf. The emf (typically a few volts) can accomplish work if an appropriate energy transducer — in this case a motor — is placed in the circuit. The motor can be coupled to a variety of mechanical devices to do useful work.

Living cells have an analogous biological “circuit,” with a relatively reduced compound such as glucose as the source of electrons. As glucose is enzymatically oxidized, the released electrons flow spontaneously through a series of electron-carrier intermediates to another chemical species, such as . This electron flow is exergonic, because has a higher affinity for electrons than do the electron-carrier intermediates. The resulting emf provides energy to a variety of molecular energy transducers (enzymes and other proteins) that do biological work. In the mitochondrion, for example, membrane-bound enzymes couple electron flow to the production of a transmembrane pH difference and a transmembrane electrical potential, accomplishing chemiosmotic and electrical work. The proton gradient thus formed has potential energy, sometimes called the proton-motive force by analogy with electromotive force. Another enzyme, ATP synthase in the inner mitochondrial membrane, uses the proton-motive force to do chemical work: synthesis of ATP from ADP and as protons flow spontaneously across the membrane. Similarly, membrane-localized enzymes in Escherichia coli convert emf to proton-motive force, which is then used to power flagellar motion. The principles of electrochemistry that govern energy changes in the macroscopic circuit with a motor and battery apply with equal validity to the molecular processes accompanying electron flow in living cells.

Oxidation-Reductions Can Be Described as Half-Reactions

Although oxidation and reduction must occur together, it is convenient when describing electron transfers to consider the two halves of an oxidation-reduction reaction separately. For example, the oxidation of ferrous ion by cupric ion,

can be described in terms of two half-reactions:

The electron-donating molecule in an oxidation-reduction reaction is called the reducing agent or reductant; the electron-accepting molecule is the oxidizing agent or oxidant. A given agent, such as an iron cation existing in the ferrous or ferric state, functions as a conjugate reductant-oxidant pair (redox pair), just as an acid and corresponding base function as a conjugate acid-base pair. Recall from Chapter 2 that in acid-base reactions we can write a general equation: proton donor proton acceptor. In redox reactions we can write a similar general equation: electron donor (reductant) electron acceptor (oxidant). In the reversible half-reaction (1) above, is the electron donor and is the electron acceptor; together, and constitute a conjugate redox pair. The mnemonic OIL RIG — oxidation is losing, reduction is gaining — may be helpful in remembering what happens to electrons in redox reactions.

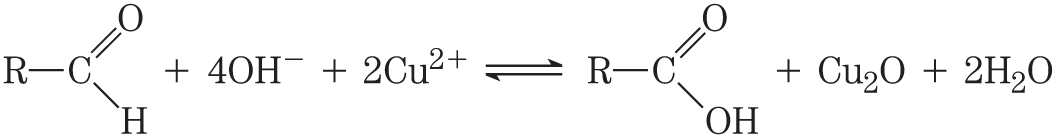

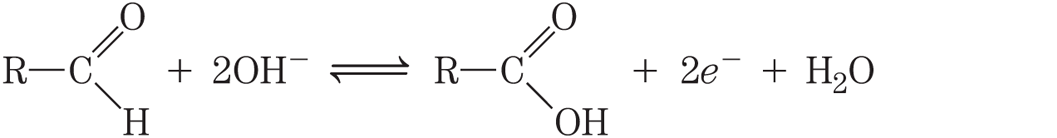

The electron transfers in the oxidation-reduction reactions of organic compounds are not fundamentally different from those of inorganic species. Consider the oxidation of a reducing sugar (an aldehyde or a ketone) by cupric ion:

This overall reaction can be expressed as two half-reactions:

Notice that because two electrons are removed from the aldehyde carbon, the second half-reaction (the one-electron reduction of cupric to cuprous ion) must be doubled to balance the overall equation.

Biological Oxidations Often Involve Dehydrogenation

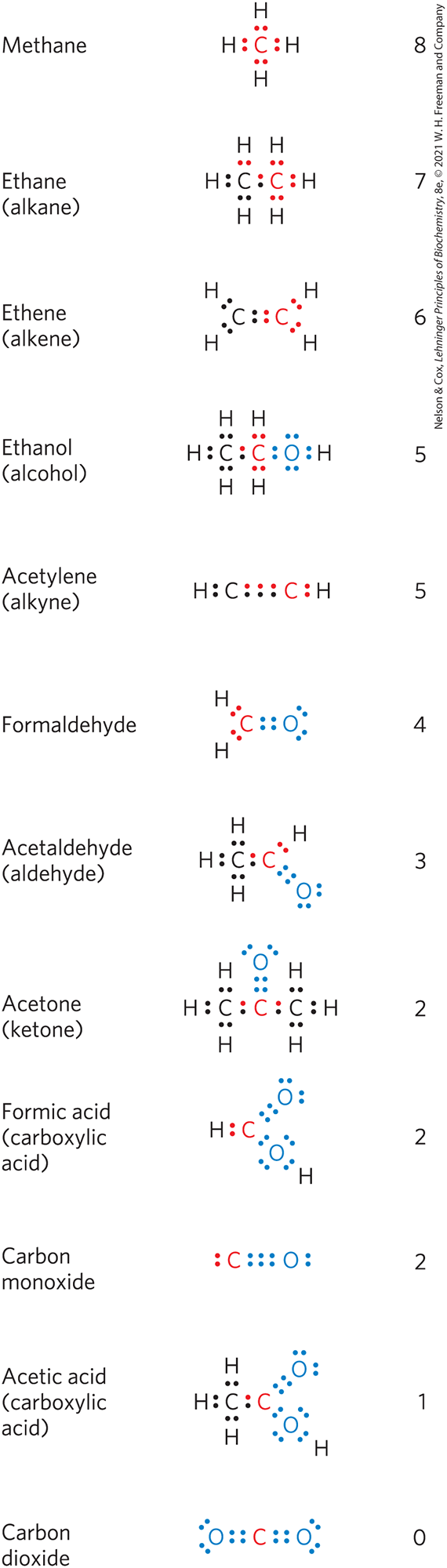

The carbon in living cells exists in a range of oxidation states (Fig. 13-22). When a carbon atom shares an electron pair with another atom (typically H, C, S, N, or O), the sharing is unequal, in favor of the more electronegative atom. The order of increasing electronegativity is . In oversimplified but useful terms, the more electronegative atom “owns” the bonding electrons it shares with another atom. For example, in methane , carbon is more electronegative than the four hydrogens bonded to it, and the C atom therefore owns all eight bonding electrons (Fig. 13-22). In ethane, the electrons in the bond are shared equally, so each C atom owns only seven of its eight bonding electrons. In ethanol, C-1 is less electronegative than the oxygen to which it is bonded, and the O atom therefore owns both electrons of the bond, leaving C-1 with only five bonding electrons. With each formal loss of “owned” electrons, the carbon atom has undergone oxidation — even when no oxygen is involved, as in the conversion of an alkane to an alkene . In this case, oxidation (loss of electrons) is coincident with the loss of hydrogen. In biological systems, as we noted earlier in the chapter, oxidation is often synonymous with dehydrogenation, and many enzymes that catalyze oxidation reactions are dehydrogenases. Notice that the more reduced compounds in Figure 13-22 (top) are richer in hydrogen than in oxygen, whereas the more oxidized compounds (bottom) have more oxygen and less hydrogen.

FIGURE 13-22 Different levels of oxidation of carbon compounds in the biosphere. To approximate the level of oxidation of these compounds, focus on the red carbon atom and its bonding electrons. When this carbon is bonded to the less electronegative H atom, both bonding electrons (red) are assigned to the carbon. When carbon is bonded to another carbon, bonding electrons are shared equally, so one of the two electrons is assigned to the red carbon. When the red carbon is bonded to the more electronegative O atom, the bonding electrons are assigned to the oxygen. The number to the right of each compound is the number of electrons “owned” by the red carbon, a rough expression of the degree of oxidation of that compound. As the red carbon undergoes oxidation (loses electrons), the number gets smaller.

Not all biological oxidation-reduction reactions involve carbon. For example, in the conversion of molecular nitrogen to ammonia, , the nitrogen atoms are reduced.

Electrons are transferred from one molecule (electron donor) to another (electron acceptor) in one of four ways:

- Directly as electrons. For example, the redox pair can transfer an electron to the redox pair:

- As hydrogen atoms. Recall that a hydrogen atom consists of a proton and a single electron . In this case we can write the general equation

where is the hydrogen/electron donor. (Do not mistake the above reaction for an acid dissociation, which involves a proton and no electron.) and A together constitute a conjugate redox pair , which can reduce another compound B (or redox pair, ) by transfer of hydrogen atoms:

- As a hydride ion , which has two electrons. This occurs in the case of NAD-linked dehydrogenases, described below.

- Through direct combination with oxygen. In this case, oxygen combines with an organic reductant and is covalently incorporated in the product, as in the oxidation of a hydrocarbon to an alcohol:

The hydrocarbon is the electron donor, and the oxygen atom is the electron acceptor.

All four types of electron transfer occur in cells. The neutral term reducing equivalent is commonly used to designate a single electron equivalent participating in an oxidation-reduction reaction, no matter whether this equivalent is an electron per se or is part of a hydrogen atom or a hydride ion, or whether the electron transfer takes place in a reaction with oxygen to yield an oxygenated product.

Reduction Potentials Measure Affinity for Electrons

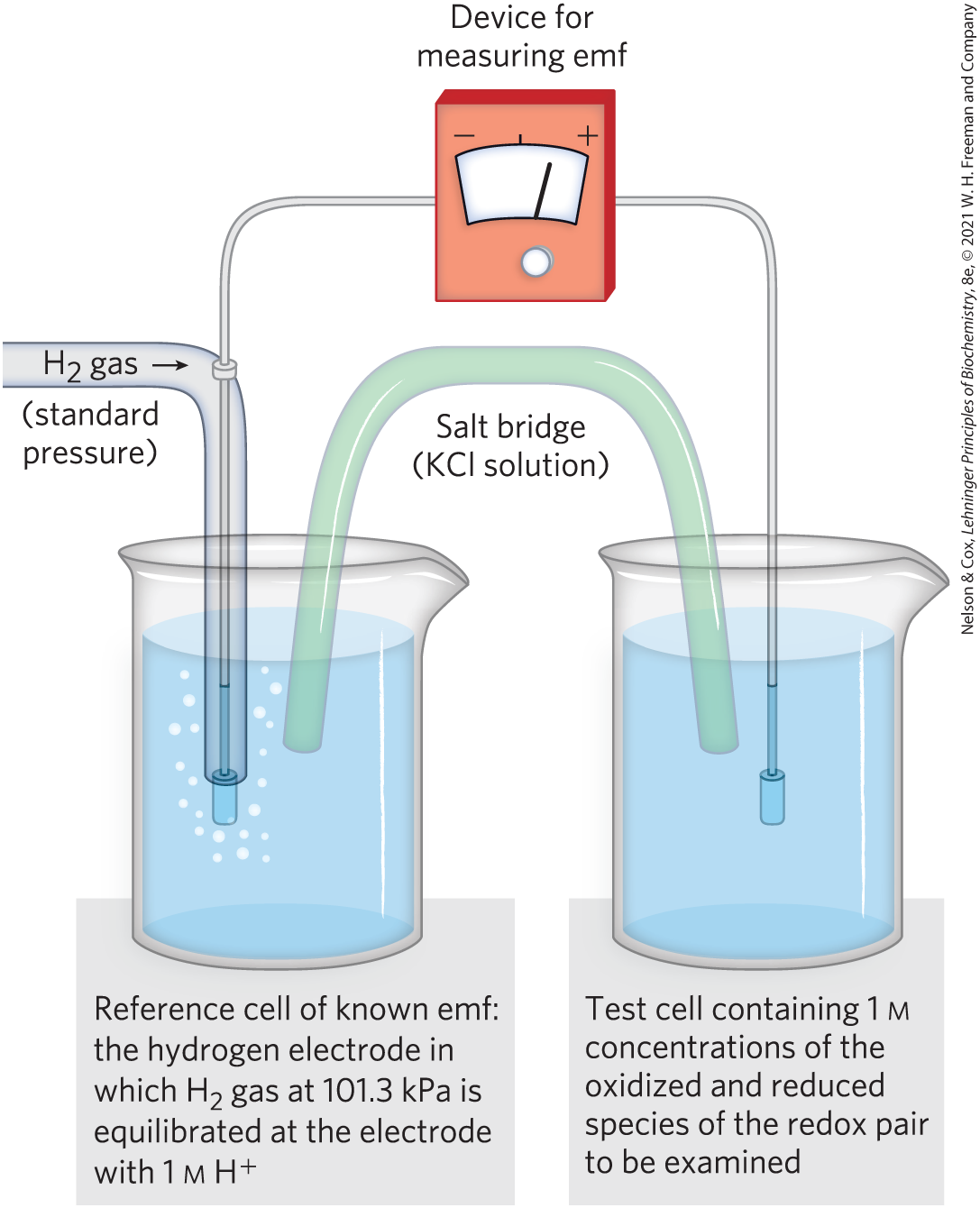

When two conjugate redox pairs are together in solution, electron transfer from the electron donor of one pair to the electron acceptor of the other may proceed spontaneously. The tendency for such a reaction depends on the relative affinity of the electron acceptor of each redox pair for electrons. The standard reduction potential, , a measure (in volts) of this affinity, can be determined in an experiment such as that described in Figure 13-23. Electrochemists have chosen as a standard of reference the half-reaction

The electrode at which this half-reaction occurs (called a half-cell) is arbitrarily assigned an of 0.00 V. When this hydrogen electrode is connected through an external circuit to another half-cell in which an oxidized species and its corresponding reduced species are present at standard concentrations (at , each solute at 1 m, each gas at 101.3 kPa), electrons tend to flow through the external circuit from the half-cell of lower to the half-cell of higher . By convention, a half-cell that takes electrons from the standard hydrogen cell is assigned a positive value of , and one that donates electrons to the hydrogen cell, a negative value. When any two half-cells are connected, that with the larger (more positive) will be reduced; it has the greater reduction potential.

FIGURE 13-23 Measurement of the standard reduction potential of a redox pair. Electrons flow from the test electrode to the reference electrode, or vice versa. The ultimate reference half-cell is the hydrogen electrode, as shown here, at pH 0. The electromotive force (emf) of this electrode is designated 0.00 V. At pH 7 in the test cell (at ), for the hydrogen electrode is . The direction of electron flow depends on the relative electron “pressure” or potential of the two cells. A salt bridge containing a saturated KCl solution provides a path for counter-ion movement between the test cell and the reference cell. From the observed emf and the known emf of the reference cell, the experimenter can find the emf of the test cell containing the redox pair. The cell that gains electrons has, by convention, the more positive reduction potential.

The reduction potential of a half-cell depends not only on the chemical species present but also on their activities, approximated by their concentrations. The Nernst equation relates standard reduction potential to the actual reduction potential (E) at any concentration of oxidized and reduced species in a living cell:

(13-5)

where R and T have their usual meanings, n is the number of electrons transferred per molecule, and F is the Faraday constant, a proportionality constant that converts volts to joules (Table 13-1). At 298 K , this expression reduces to

(13-6)

Key convention

Many half-reactions of interest to biochemists involve protons. As in the definition of , biochemists define the standard state for oxidation-reduction reactions as pH 7 and express a standard transformed reduction potential, , the standard reduction potential at pH 7 and . By convention, for any redox reaction is given as of the electron acceptor minus of the electron donor.

The standard reduction potentials given in Table 13-7 and used throughout this book are values for and are therefore valid only for systems at neutral pH. Each value represents the potential difference when the conjugate redox pair, at 1 m concentrations, , and pH 7, is connected with the standard (pH 0) hydrogen electrode. Notice in Table 13-7 that when the conjugate pair at pH 7 is connected with the standard hydrogen electrode (pH 0), electrons tend to flow from the pH 7 cell to the standard (pH 0) cell; the measured for the pair is –0.414 V.

| Half-reaction | (V) |

|---|---|

0.816 |

|

0.771 |

|

0.421 |

|

0.365 |

|

0.36 |

|

0.35 |

|

0.295 |

|

0.29 |

|

0.254 |

|

0.22 |

|

0.077 |

|

0.045 |

|

0.031 |

|

(at standard conditions, pH 0) |

0.000 |

|

Data mostly from R. A. Loach, in Handbook of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 3rd edn (G. D. Fasman, ed.), Physical and Chemical Data, Vol. 1, p. 122, CRC Press, 1976. aThis is the value for free FAD; FAD bound to a specific flavoprotein (e.g., succinate dehydrogenase) has a different that depends on its protein environment. |

|

Standard Reduction Potentials Can Be Used to Calculate Free-Energy Change

Why are reduction potentials so useful to the biochemist? When E values have been determined for any two half-cells, relative to the standard hydrogen electrode, we also know their reduction potentials relative to each other. We can then predict the direction in which electrons will tend to flow when the two half-cells are connected through an external circuit or when components of both half-cells are present in the same solution. Electrons tend to flow to the half-cell with the more positive E, and the strength of that tendency is proportional to ∆E, the difference in reduction potential. The energy made available by this spontaneous electron flow (the free-energy change, ∆G, for the oxidation-reduction reaction) is proportional to ∆E:

(13-7)

where n is the number of electrons transferred in the reaction. With this equation we can calculate the actual free-energy change for any oxidation-reduction reaction from the values of in a table of reduction potentials (Table 13-7) and the concentrations of reacting species.

WORKED EXAMPLE 13-3 Calculation of and ΔG of a Redox Reaction

Calculate the standard free-energy change, , for the reaction in which acetaldehyde is reduced by the biological electron carrier NADH:

Then calculate the actual free-energy change, ∆G, when [acetaldehyde] and [NADH] are 1.00 m, and [ethanol] and are 0.100 m. The relevant half-reactions and their values are

Remember that, by convention, is of the electron acceptor minus of the electron donor. It represents the difference between the electron affinities of the two half-reactions in the table of reduction potentials (Table 13-7). Note that the more widely separated the two half-reactions in the table, the more energetic the electron-transfer reaction when the two half-reactions occur together. By convention, in tables of reduction potentials, all half-reactions are represented as reductions, but when two half-reactions occur together, one of them must be an oxidation. Although that half-reaction will go in the opposite direction from that shown in Table 13-7, we do not change the sign of that half-reaction before calculating , because is defined as a difference of reduction potentials.

SOLUTION:

Because acetaldehyde is accepting electrons from NADH, . Therefore,

This is the free-energy change for the oxidation-reduction reaction at and pH 7, when acetaldehyde, ethanol, , and NADH are all present at 1.00 m concentrations.

To calculate ΔG when [acetaldehyde] and [NADH] are 1.00 m, and [ethanol] and are 0.100 m, we can use Equation 13-4 and the standard free-energy change calculated above:

This is the actual free-energy change at the specified concentrations of the redox pairs.

A Few Types of Coenzymes and Proteins Serve as Universal Electron Carriers

The principles of oxidation-reduction energetics described above apply to the many metabolic reactions that involve electron transfers. For example, in many organisms, the oxidation of glucose supplies energy for the production of ATP. The complete oxidation of glucose

has a of . This is a much larger release of free energy than is required for ATP synthesis in cells (50 to 60 kJ/mol; see Worked Example 13-2). Cells convert glucose to not in a single, high-energy-releasing reaction but rather in a series of controlled reactions, some of which are oxidations. The free energy released in these oxidation steps is of the same order of magnitude as that required for ATP synthesis from ADP, with some energy to spare. Electrons removed in these oxidation steps are transferred to coenzymes specialized for carrying electrons, such as and FAD (described below).

The multitude of enzymes that catalyze cellular oxidations channel electrons from their hundreds of different substrates into just a few types of universal electron carriers. The reduction of these carriers in catabolic processes results in the conservation of free energy released by substrate oxidation. NAD, NADP, FMN, and FAD are water-soluble coenzymes that undergo reversible oxidation and reduction in many of the electron-transfer reactions of metabolism. The nucleotides NAD and NADP move readily from one enzyme to another; the flavin nucleotides FMN and FAD are usually very tightly bound to the enzymes, called flavoproteins, for which they serve as prosthetic groups. Lipid-soluble quinones such as ubiquinone and plastoquinone act as electron carriers and proton donors in the nonaqueous environment of membranes. Iron-sulfur proteins and cytochromes, which have tightly bound prosthetic groups that undergo reversible oxidation and reduction, also serve as electron carriers in many oxidation-reduction reactions. Some of these proteins are water-soluble, but others are peripheral or integral membrane proteins. The oxidation-reduction chemistry of quinones, iron-sulfur proteins, and cytochromes is discussed in Chapters 19 and 20.

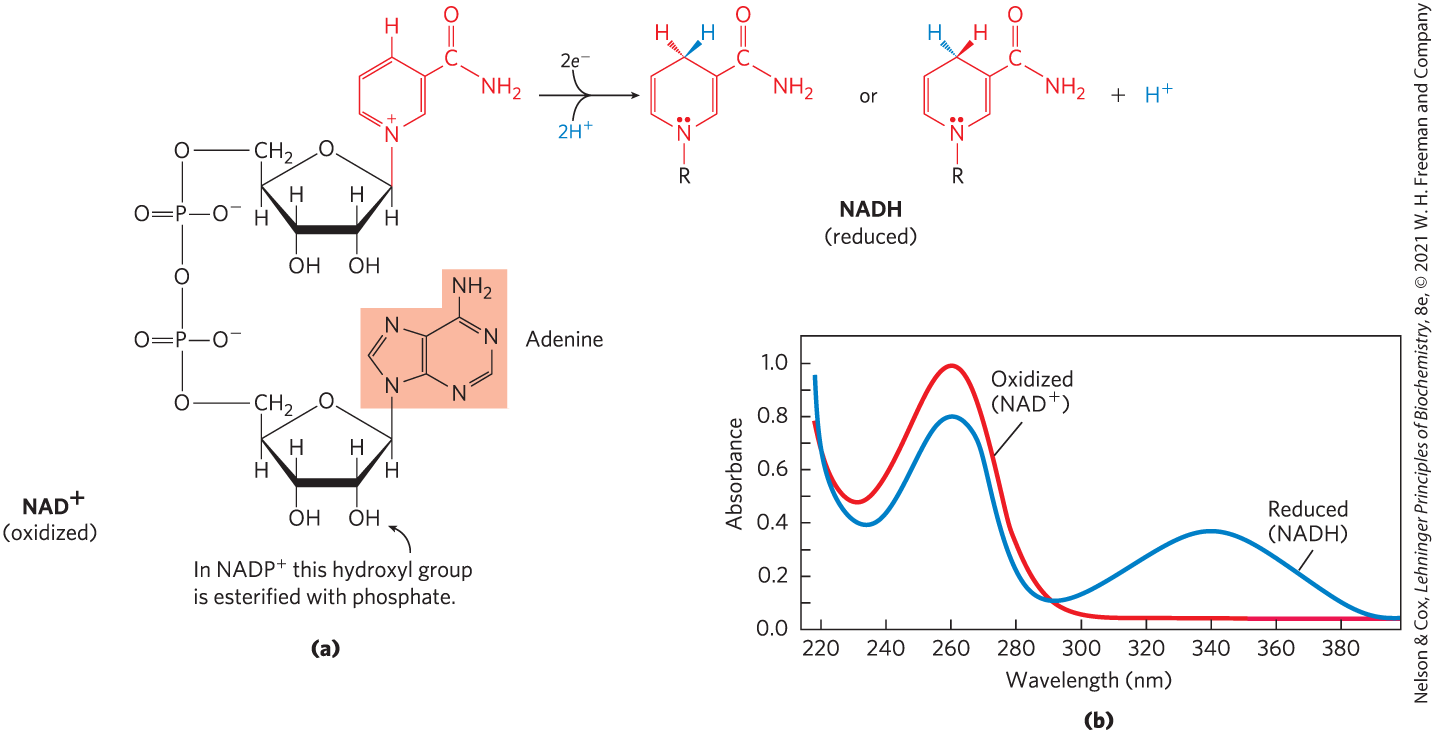

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD; in its oxidized form) and its close analog nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP; when oxidized) are composed of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups by a phosphoanhydride bond (Fig. 13-24a). Because the nicotinamide ring resembles pyridine, these compounds are sometimes called pyridine nucleotides. The vitamin niacin is the source of the nicotinamide moiety in nicotinamide nucleotides.

FIGURE 13-24 NAD and NADP. (a) Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, , and its phosphorylated analog, , undergo reduction to NADH and NADPH, accepting a hydride ion (two electrons and one proton) from an oxidizable substrate. The hydride ion is added to either the front or the back of the planar nicotinamide ring. (b) The UV absorption spectra of and NADH. Reduction of the nicotinamide ring produces a new, broad absorption band with a maximum at 340 nm. The production of NADH during an enzyme-catalyzed reaction can be conveniently followed by observing the appearance of the absorbance at 340 nm (molar extinction coefficient ).

Both coenzymes undergo reversible reduction of the nicotinamide ring (Fig. 13-24). As a substrate molecule undergoes oxidation (dehydrogenation), giving up two hydrogen atoms, the oxidized form of the nucleotide accepts a hydride ion (, the equivalent of a proton and two electrons) and is reduced (to NADH or NADPH). The second proton removed from the substrate is released to the aqueous solvent. The half-reactions for these nucleotide cofactors are

Reduction of or converts the benzenoid ring of the nicotinamide moiety (with a fixed positive charge on the ring nitrogen) to the quinonoid form (with no charge on the nitrogen). The reduced nucleotides absorb light at 340 nm; the oxidized forms do not (Fig. 13-24b). Biochemists use this difference in absorption to assay reactions involving these coenzymes. Note that the plus sign in the abbreviations and does not indicate the net charge on these molecules (in fact, both are negatively charged); rather, it indicates that the nicotinamide ring is in its oxidized form, with a positive charge on the nitrogen atom. In the abbreviations NADH and NADPH, the “H” denotes the added hydride ion. To refer to these nucleotides without specifying their oxidation state, we use NAD and NADP.

The total concentration of in most tissues is about ; that of is about . In many cells and tissues, the ratio of (oxidized) to NADH (reduced) is high, favoring hydride transfer from a substrate to to form NADH. By contrast, NADPH is generally present at a higher concentration than , favoring hydride transfer from NADPH to a substrate. This reflects the specialized metabolic roles of the two coenzymes: generally functions in oxidations — usually as part of a catabolic reaction; NADPH is the usual coenzyme in reductions — nearly always as part of an anabolic reaction. A few enzymes can use either coenzyme, but most show a strong preference for one over the other. Also, the processes in which these two cofactors function are segregated in eukaryotic cells: for example, oxidations of fuels such as pyruvate, fatty acids, and α-keto acids derived from amino acids occur in the mitochondrial matrix, whereas reductive biosynthetic processes such as fatty acid synthesis take place in the cytosol. This functional and spatial specialization allows a cell to maintain two distinct pools of electron carriers, with two distinct functions.

More than 200 enzymes are known to catalyze reactions in which (or ) accepts a hydride ion from a reduced substrate, or NADPH (or NADH) donates a hydride ion to an oxidized substrate. The general reactions are

where is the reduced substrate and A is the oxidized substrate. The general name for an enzyme of this type is oxidoreductase; they are also commonly called dehydrogenases. For example, alcohol dehydrogenase catalyzes the first step in the catabolism of ethanol, in which ethanol is oxidized to acetaldehyde:

Notice that one of the carbon atoms in ethanol has lost a hydrogen; the compound has been oxidized from an alcohol to an aldehyde (refer again to Fig. 13-22 for the oxidation states of carbon).

The association between a dehydrogenase and NAD or NADP is relatively loose; the coenzyme readily diffuses from one enzyme to another, acting as a water-soluble carrier of electrons from one metabolite to another. For example, in the production of alcohol during fermentation of glucose by yeast cells, a hydride ion is removed from glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate by one enzyme (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) and transferred to . The NADH produced then leaves the enzyme surface and diffuses to another enzyme (alcohol dehydrogenase), which transfers a hydride ion to acetaldehyde, producing ethanol:

Notice that in the overall reaction there is no net production or consumption of or NADH; the coenzymes function catalytically and are recycled repeatedly without a net change in the total amount of .

Both reduced and oxidized forms of NAD and NADP serve as allosteric effectors of proteins in catabolic pathways. As we describe in later chapters, the ratios and serve as sensitive gauges of a cell’s fuel supply, allowing rapid, appropriate changes in energy-yielding and energy-dependent metabolism.

NAD Has Important Functions in Addition to Electron Transfer

Some key cellular functions are regulated by enzymes that use not as a redox cofactor but as a substrate in a coupled reaction in which the availability of can be an indicator of the cell’s energy status. In DNA replication and repair, the enzyme DNA ligase is adenylylated and then transfers the AMP to a phosphate in a nicked DNA (see Fig. 25-15); in bacteria, serves as the source of the activating AMP group. A family of proteins called sirtuins regulate the activity of proteins in diverse cellular pathways by deacetylating the -amino group of an acetylated Lys residue. The deacetylation is coupled to hydrolysis, yielding O-acetyl-ADP-ribose and nicotinamide. Among the cellular processes regulated by sirtuins are inflammation, apoptosis, aging, and DNA transcription; deacetylation by a sirtuin alters the charge on histones, influencing which genes are expressed. The availability of for these types of reactions may indicate that the cell is undergoing stress and that pathways designed to respond to stress should be activated.

also plays an important role in cholera pathology (see Section 12.2). Cholera toxin has an enzymatic activity that transfers ADP-ribose from to a G protein involved in regulating ion fluxes in the cells lining the gut. This ADP-ribosylation blocks water retention, causing the diarrhea and dehydration characteristic of cholera.

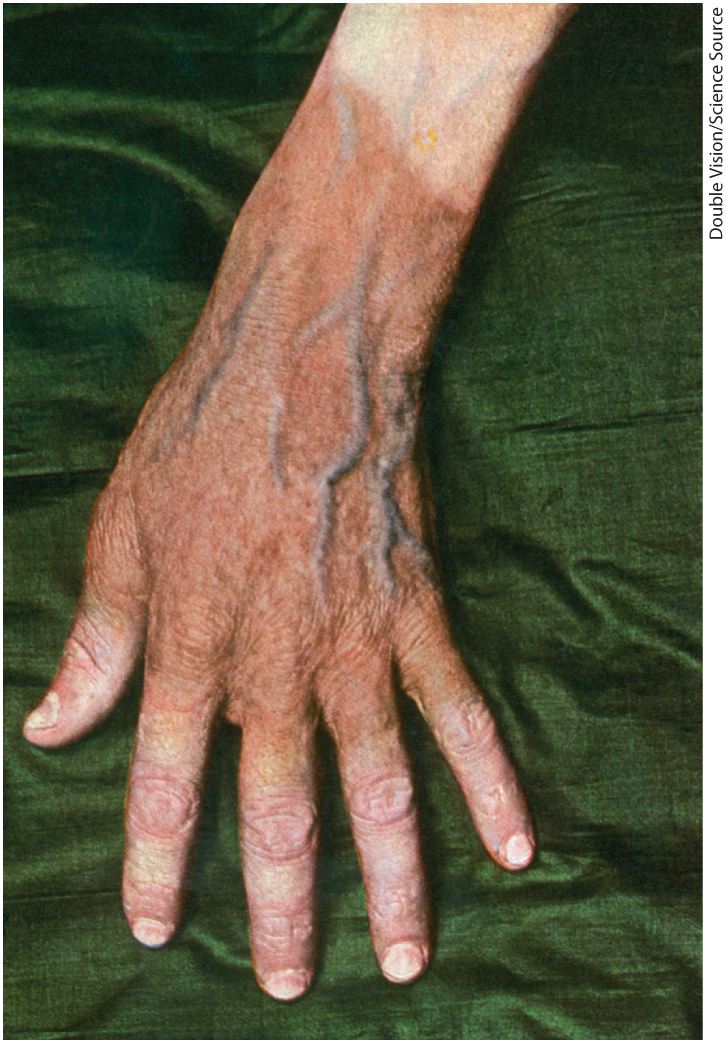

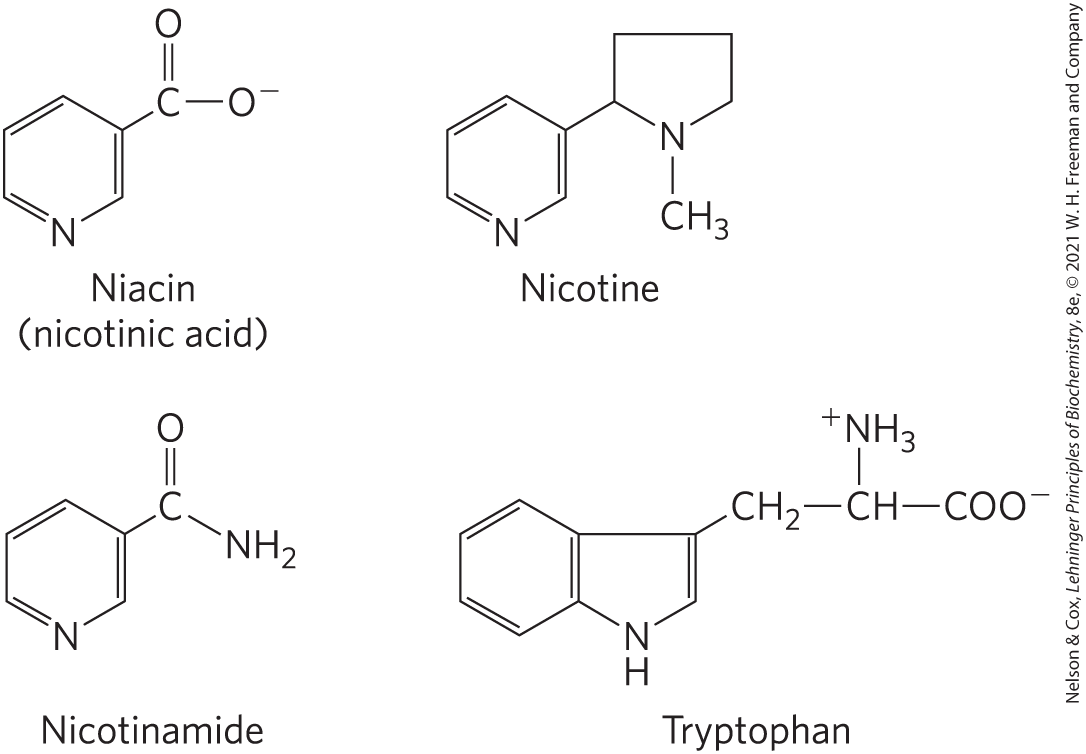

Dietary deficiency of niacin, the vitamin form of NAD and NADP, causes pellagra (Fig. 13-25). The pyridine-like rings of NAD and NADP are derived from the vitamin niacin (nicotinic acid; Fig. 13-26), which is synthesized from tryptophan. Humans generally cannot synthesize sufficient quantities of niacin, and this is especially so for individuals with diets low in tryptophan (maize, for example, has a low tryptophan content). Niacin deficiency, which affects all the NAD(P)-dependent dehydrogenases, causes the serious human disease pellagra (Italian for “rough skin”) and a related disease in dogs, called black tongue. Pellagra is characterized by the “three Ds”: dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia, followed in many cases by death. A century ago, pellagra was a common human disease; in the southern United States, where maize was a dietary staple, about 100,000 people were afflicted and about 10,000 died as a result of this disease between 1912 and 1916. In 1920, Joseph Goldberger showed pellagra to be caused by a dietary insufficiency, and in 1937, Frank Strong, D. Wayne Woolley, and Conrad Elvehjem identified niacin as the curative agent for the dog version of pellagra, black tongue. Supplementation of the human diet with this inexpensive compound has nearly eradicated pellagra in the populations of the developed world, with one significant exception: people who drink excessive amounts of alcohol. In these individuals, intestinal absorption of niacin is much reduced, and caloric needs are often met with distilled spirits that are virtually devoid of vitamins, including niacin.

FIGURE 13-25 Dermatitis associated with pellagra. Dermatitis involving the face, hands, and feet is an early sign of pellagra, a serious human disease that results from insufficient niacin in the diet. Untreated, pellagra leads to dementia and ultimately is fatal.

FIGURE 13-26 Niacin (nicotinic acid) and its derivative nicotinamide. The biosynthetic precursor of these compounds is tryptophan. In the laboratory, nicotinic acid was first produced by oxidation of the natural product nicotine—thus the name. Both nicotinic acid and nicotinamide cure pellagra, but nicotine (from cigarettes or elsewhere) has no curative activity.

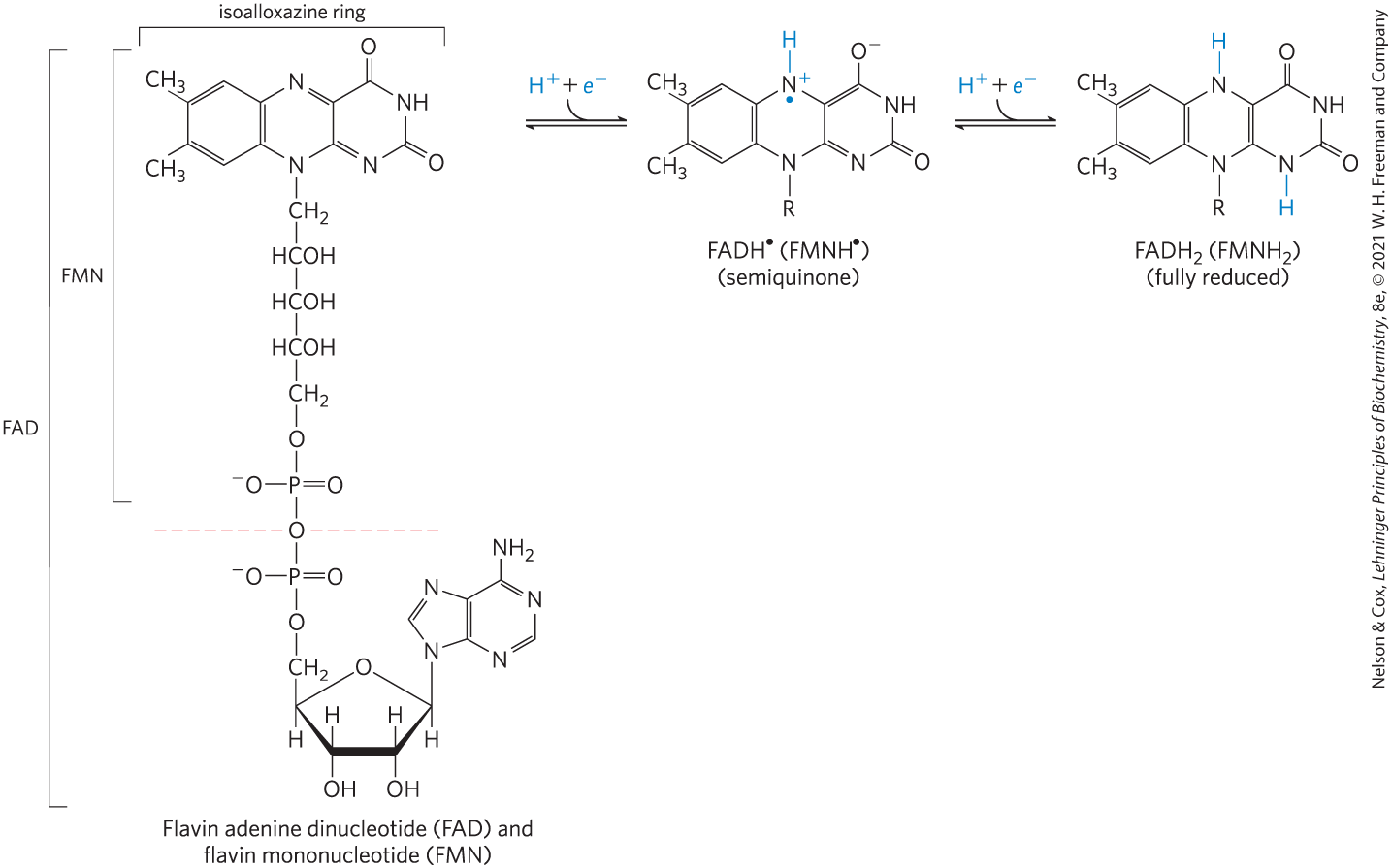

Flavin Nucleotides Are Tightly Bound in Flavoproteins

Flavoproteins are enzymes that catalyze oxidation-reduction reactions using either flavin mononucleotide (FMN) or flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as coenzyme (Fig. 13-27). These coenzymes, the flavin nucleotides, are derived from the vitamin riboflavin. The fused ring structure of flavin nucleotides (the isoalloxazine ring) undergoes reversible reduction, accepting either one or two electrons in the form of one or two hydrogen atoms (each atom an electron plus a proton) from a reduced substrate. The fully reduced forms are abbreviated and . When a fully oxidized flavin nucleotide accepts only one electron (one hydrogen atom), the semiquinone form of the isoalloxazine ring is produced, abbreviated and . Because flavin nucleotides have a chemical specialty that is slightly different from that of the nicotinamide coenzymes — the ability to participate in either one- or two-electron transfers — flavoproteins are involved in a greater diversity of reactions than the NAD(P)-linked dehydrogenases.

FIGURE 13-27 Oxidized and reduced FAD and FMN. FMN consists of the structure above the dashed red line across the FAD molecule (oxidized form). The flavin nucleotides accept two hydrogen atoms (two electrons and two protons), both of which appear in the flavin ring system (isoalloxazine ring). When FAD or FMN accepts only one hydrogen atom, the semiquinone, a stable free radical, forms.

Like the nicotinamide coenzymes (Fig. 13-24), the flavin nucleotides undergo a shift in a major absorption band on reduction (again, useful to biochemists who want to monitor reactions involving these coenzymes). Flavoproteins that are fully reduced (two electrons accepted) generally have an absorption maximum near 360 nm. When partially reduced (one electron), they acquire another absorption maximum at about 450 nm; when fully oxidized, the flavin has maxima at 370 and 440 nm.

The flavin nucleotide in most flavoproteins is bound rather tightly to the protein, and in some enzymes, such as succinate dehydrogenase, it is bound covalently. Such tightly bound coenzymes are properly called prosthetic groups. They do not transfer electrons by diffusing from one enzyme to another; rather, they provide a means by which the flavoprotein can temporarily hold electrons while it catalyzes electron transfer from a reduced substrate to an electron acceptor. One important feature of the flavoproteins is the variability in the standard reduction potential of the bound flavin nucleotide. Tight association between the enzyme and prosthetic group confers on the flavin ring a reduction potential typical of that particular flavoprotein, sometimes quite different from the reduction potential of the free flavin nucleotide. FAD bound to succinate dehydrogenase, for example, has an close to 0.0 V, compared with for free FAD; for other flavoproteins ranges from Flavoproteins are often very complex; some have, in addition to a flavin nucleotide, tightly bound inorganic ions (iron or molybdenum, for example) capable of participating in electron transfers.

We examine the function of flavoproteins as electron carriers in Chapters 19 and 20, when we consider their roles in oxidative phosphorylation (in mitochondria) and photophosphorylation (in chloroplasts).

SUMMARY 13.4 Biological Oxidation-Reduction Reactions

- In many organisms, a central energy-conserving process is the stepwise oxidation of glucose to , in which some of the energy of oxidation is conserved in ATP as electrons are passed to .

- Biological oxidation-reduction reactions can be described in terms of two half-reactions, each with a characteristic standard reduction potential, .

- Many biological oxidation reactions are dehydrogenations in which one or two hydrogen atoms are transferred from a substrate to a hydrogen acceptor. In some biological redox reactions, the substrate loses both electrons and protons, the equivalent of losing hydrogen. The many enzymes that catalyze such reactions are called dehydrogenases.

- When two electrochemical half-cells, each containing the components of a half-reaction, are connected, electrons tend to flow to the half-cell with the higher reduction potential. The strength of this tendency is proportional to the difference between the two reduction potentials (∆E) and is a function of the concentrations of oxidized and reduced species.

- The standard free-energy change for an oxidation-reduction reaction is directly proportional to the difference in standard reduction potentials of the two half-cells: .

- Oxidation-reduction reactions in living cells involve specialized electron carriers. NAD and NADP are the freely diffusible coenzymes of many dehydrogenases. Both and accept two electrons and one proton. In addition to its role in oxidation-reduction reactions, is the source of AMP in the bacterial DNA ligase reaction and of ADP-ribose in the cholera toxin reaction, and it is hydrolyzed in the deacetylation of proteins by some sirtuins.

- Lack of the vitamin niacin prevents NAD synthesis and leads to pellagra.

- FAD and FMN, the flavin nucleotides, serve as tightly bound prosthetic groups of flavoproteins. They can accept either one or two electrons and one or two protons. Their reduction potentials depend on the flavoprotein with which they are associated.

The flow of electrons in oxidation-reduction reactions is responsible, directly or indirectly, for all work done by living organisms. In nonphotosynthetic organisms, the sources of electrons are reduced compounds (foods); in photosynthetic organisms, the initial electron donor is a chemical species excited by the absorption of light. The path of electron flow in metabolism is complex. Electrons move from various metabolic intermediates to specialized electron carriers in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. The carriers, in turn, donate electrons to acceptors with higher electron affinities, with the release of energy. Cells possess a variety of molecular energy transducers, which convert the energy of electron flow into useful work.

The flow of electrons in oxidation-reduction reactions is responsible, directly or indirectly, for all work done by living organisms. In nonphotosynthetic organisms, the sources of electrons are reduced compounds (foods); in photosynthetic organisms, the initial electron donor is a chemical species excited by the absorption of light. The path of electron flow in metabolism is complex. Electrons move from various metabolic intermediates to specialized electron carriers in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. The carriers, in turn, donate electrons to acceptors with higher electron affinities, with the release of energy. Cells possess a variety of molecular energy transducers, which convert the energy of electron flow into useful work.

In many organisms, a central energy-conserving process is the stepwise oxidation of glucose to , in which some of the energy of oxidation is conserved in ATP as electrons are passed to .

In many organisms, a central energy-conserving process is the stepwise oxidation of glucose to , in which some of the energy of oxidation is conserved in ATP as electrons are passed to .