1.1 Cellular Foundations

The unity and diversity of organisms become apparent even at the cellular level. The smallest organisms consist of single cells and are microscopic. Larger, multicellular organisms contain many different types of cells, which vary in size, shape, and specialized function. Despite these obvious differences, all cells of the simplest and most complex organisms share certain fundamental properties, which can be seen at the biochemical level.

Cells Are the Structural and Functional Units of All Living Organisms

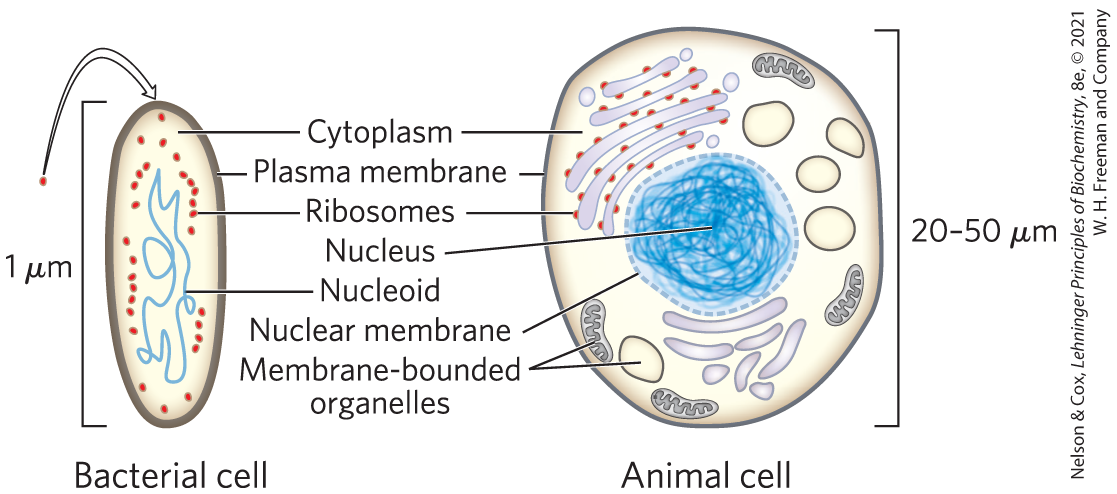

Cells of all kinds share certain structural features (Fig. 1-1). The plasma membrane defines the periphery of the cell, separating its contents from the surroundings. It is composed of lipid and protein molecules that form a thin, tough, pliable, hydrophobic barrier around the cell. The membrane is a barrier to the free passage of inorganic ions and most other charged or polar molecules. Transport proteins in the plasma membrane allow the passage of certain ions and molecules, receptor proteins transmit signals into the cell, and membrane enzymes participate in some reaction pathways. Because the individual lipids and proteins of the plasma membrane are not covalently linked, the entire structure is remarkably flexible, allowing changes in the shape and size of the cell. As a cell grows, newly made lipid and protein molecules are inserted into its plasma membrane; cell division produces two cells, each with its own membrane. This growth and cell division (fission) occurs without loss of membrane integrity.

FIGURE 1-1 The universal features of living cells. All cells have a nucleus or nucleoid containing their DNA, a plasma membrane, and cytoplasm. Eukaryotic cells contain a variety of membrane-bounded organelles (including mitochondria and chloroplasts) and large particles (ribosomes, for example).

The internal volume enclosed by the plasma membrane, the cytoplasm (Fig. 1-1), is composed of an aqueous solution, the cytosol, and a variety of suspended particles with specific functions. These particulate components (membranous organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts; supramolecular structures such as ribosomes and proteasomes, the sites of protein synthesis and degradation) sediment when cytoplasm is centrifuged at 150,000 g (g is the gravitational force of Earth). What remains as the supernatant fluid is defined as the cytosol, a highly concentrated solution containing enzymes and the RNA (ribonucleic acid) molecules that encode them; the components (amino acids and nucleotides) from which these macromolecules are assembled; hundreds of small organic molecules called metabolites, intermediates in biosynthetic and degradative pathways; coenzymes, compounds essential to many enzyme-catalyzed reactions; and inorganic ions ( and for example).

All cells have, for at least some part of their life, either a nucleoid or a nucleus, in which the genome — the complete set of genes, composed of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) — is replicated and stored, with its associated proteins. The nucleoid, in bacteria and archaea, is not separated from the cytoplasm by a membrane; the nucleus, in eukaryotes, is enclosed within a double membrane, the nuclear envelope. Cells with nuclear envelopes make up the large domain Eukarya (Greek eu, “true,” and karyon, “nucleus”). Microorganisms without nuclear membranes, formerly grouped together as prokaryotes (Greek pro, “before”), are now recognized as comprising two very distinct groups: the domains Bacteria and Archaea, described below.

Cellular Dimensions Are Limited by Diffusion

Most cells are microscopic, invisible to the unaided eye. Animal and plant cells are typically 5 to 100 μm in diameter, and many unicellular microorganisms are only 1 to 2 μm long (see the inside of the back cover for information on units and their abbreviations). What limits the dimensions of a cell? The lower limit is probably set by the minimum number of each type of biomolecule required by the cell. The smallest cells, certain bacteria known as mycoplasmas, are 300 nm in diameter and have a volume of about A single bacterial ribosome is about 20 nm in its longest dimension, so a few ribosomes take up a substantial fraction of the volume in a mycoplasmal cell.

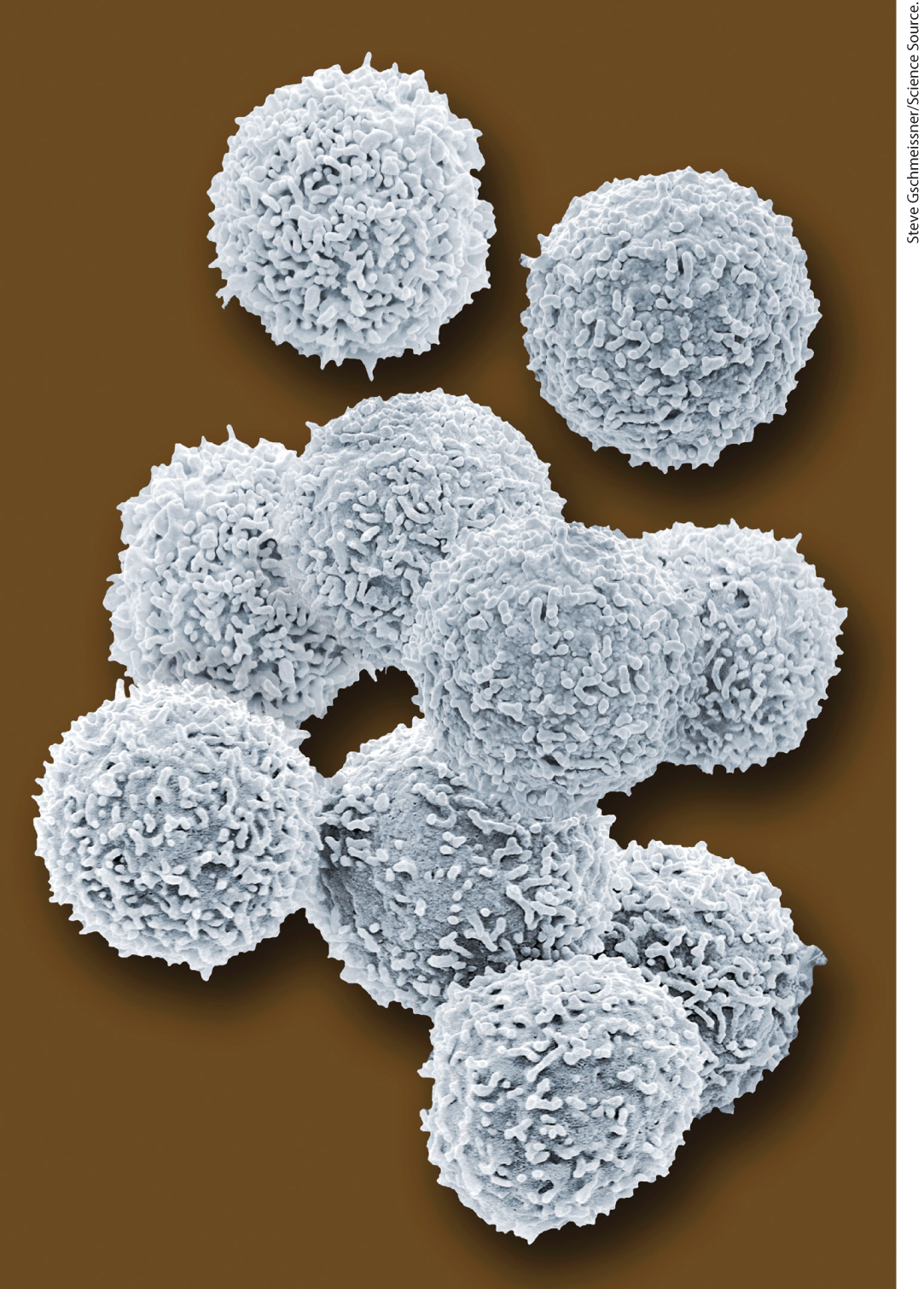

The upper limit of cell size is probably set by the rate of transport of nutrients into the cell and waste products out. As the size of a cell increases, its surface-to-volume ratio decreases. For a spherical cell, the surface area is a function of the square of the radius whereas its volume is a function of A bacterial cell the size of Eschericia coli is so small, and the ratio of its surface area to its volume is so large, that every part of its cytoplasm is easily reached by nutrients moving across the membrane and into the cell. With increasing cell size, surface-to-volume ratio decreases, until metabolism consumes nutrients faster than transmembrane carriers can supply them. Many types of animal cells have a highly folded or convoluted surface that increases their surface-to-volume ratio and allows higher rates of uptake of materials from their surroundings (Fig. 1-2).

FIGURE 1-2 Most animal cells have intricately folded surfaces. The human lymphocytes in this artificially colored scanning electron micrograph are about 10–12 μm in diameter. Their convoluted surfaces give them a much larger surface area than a sphere of the same diameter.

Organisms Belong to Three Distinct Domains of Life

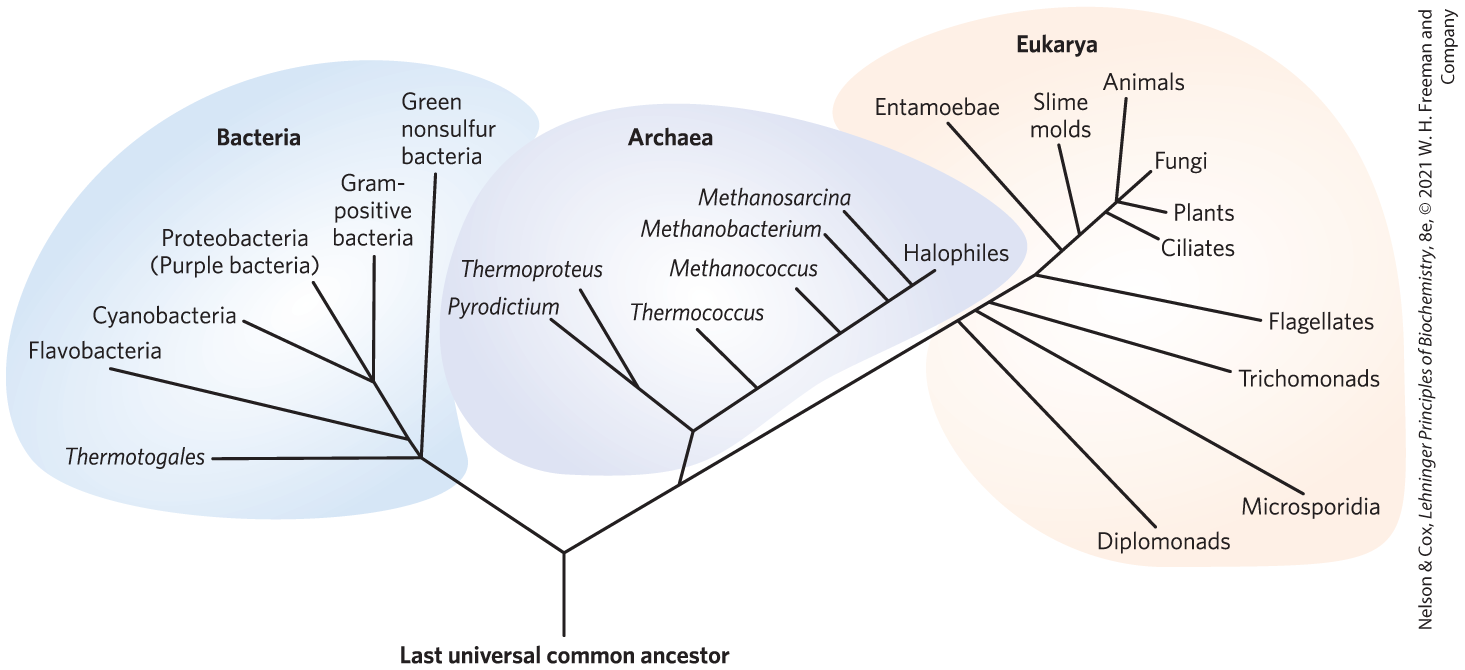

The development of techniques for determining DNA sequences quickly and inexpensively has greatly improved our ability to deduce evolutionary relationships among organisms. Similarities between gene sequences in various organisms provide deep insight into the course of evolution. In one interpretation of sequence similarities, all living organisms fall into one of three large groups (domains) that define three branches of the evolutionary tree of life originating from a common progenitor (Fig. 1-3). Two large groups of single-celled microorganisms can be distinguished on genetic and biochemical grounds: Bacteria and Archaea. Bacteria inhabit soils, surface waters, and the tissues of other living or decaying organisms. Many of the Archaea, recognized as a distinct domain by the microbiologist Carl Woese in the 1980s, inhabit extreme environments — salt lakes, hot springs, highly acidic bogs, and the ocean depths. The available evidence suggests that the Archaea and Bacteria diverged early in evolution. All eukaryotic organisms, which make up the third domain, Eukarya, evolved from the same branch that gave rise to the Archaea; eukaryotes are therefore more closely related to archaea than to bacteria.

FIGURE 1-3 Phylogeny of the three domains of life. Phylogenetic relationships are often illustrated by a “family tree” of this type. The basis for this tree is the similarity in nucleotide sequences of the ribosomal RNAs of each group. [Information from C. R. Woese, Microbiol. Rev. 51:221, 1987, Fig. 4.]

Within the domains of Archaea and Bacteria are subgroups distinguished by their habitats. In aerobic habitats with a plentiful supply of oxygen, some resident organisms derive energy from the transfer of electrons from fuel molecules to oxygen within the cell. Other environments are anaerobic, devoid of oxygen, and microorganisms adapted to these environments obtain energy by transferring electrons to nitrate (forming ), sulfate (forming ), or (forming ). Many organisms that have evolved in anaerobic environments are obligate anaerobes: they die when exposed to oxygen. Others are facultative anaerobes, able to live with or without oxygen.

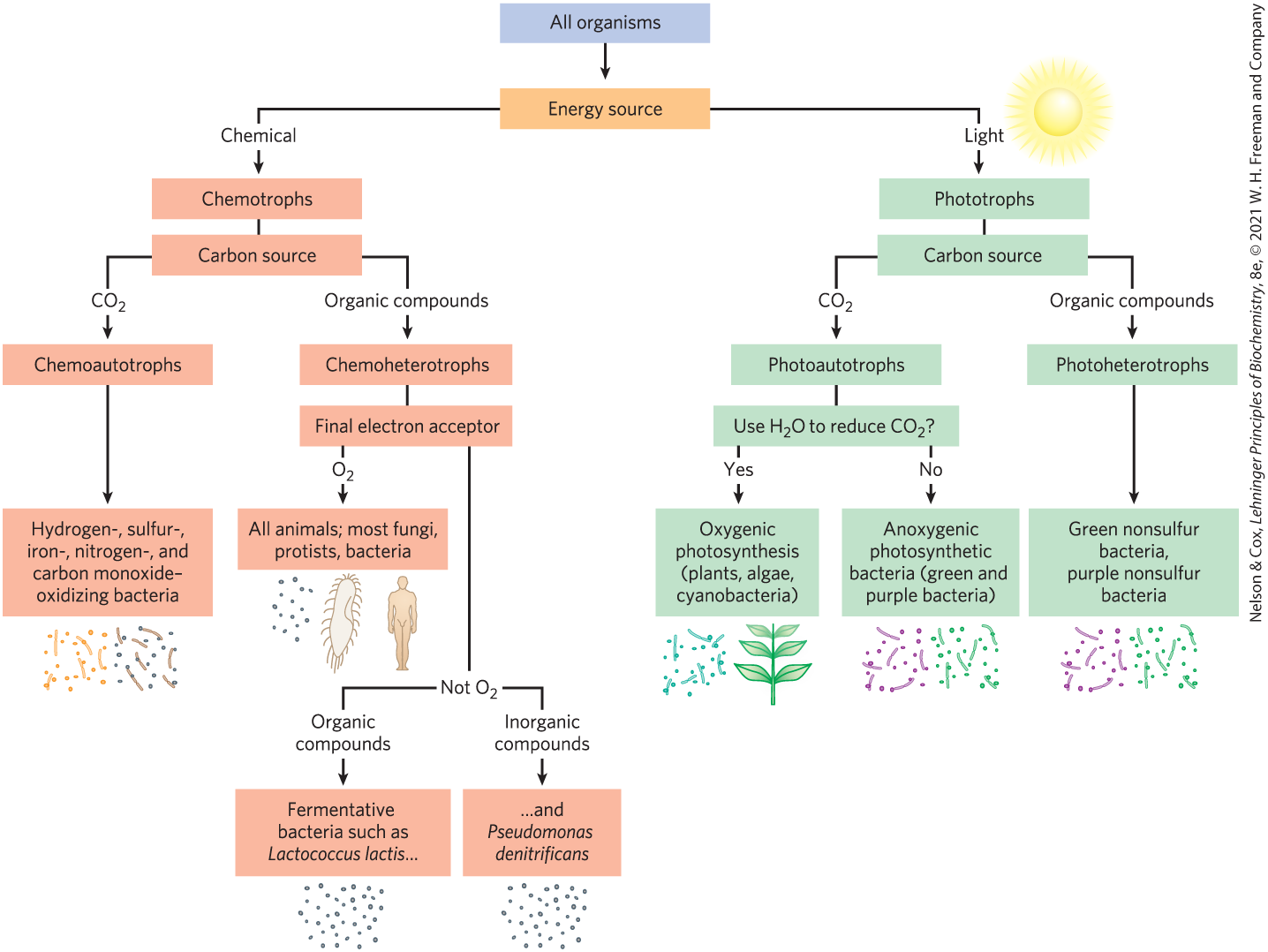

Organisms Differ Widely in Their Sources of Energy and Biosynthetic Precursors

We can classify organisms according to how they obtain the energy and carbon they need for synthesizing cellular material (as summarized in Fig. 1-4). There are two broad categories based on energy sources: phototrophs (Greek trophē, “nourishment”) trap and use sunlight, and chemotrophs derive their energy from oxidation of a chemical fuel. Some chemotrophs oxidize inorganic fuels — to (elemental sulfur), to to or to for example. Phototrophs and chemotrophs may be further divided into those that can synthesize all of their biomolecules directly from (autotrophs) and those that require some preformed organic nutrients made by other organisms (heterotrophs). We can describe an organism’s mode of nutrition by combining these terms. For example, cyanobacteria are photoautotrophs; humans are chemoheterotrophs. Even finer distinctions can be made, and many organisms can obtain energy and carbon from more than one source under different environmental or developmental conditions.

FIGURE 1-4 All organisms can be classified according to their source of energy (sunlight or oxidizable chemical compounds) and their source of carbon for the synthesis of cellular material.

Bacterial and Archaeal Cells Share Common Features but Differ in Important Ways

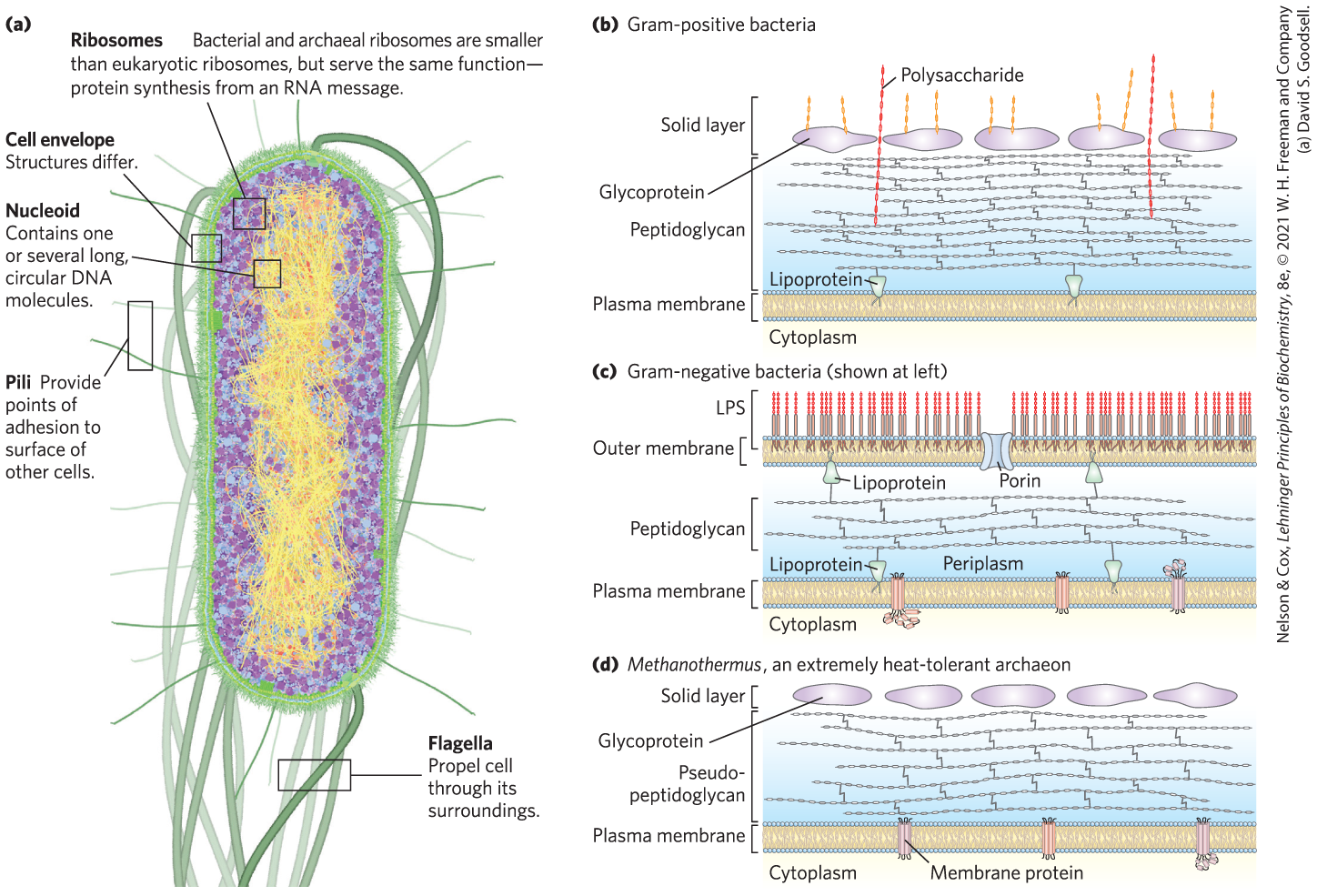

The best-studied bacterium, Escherichia coli, is a usually harmless inhabitant of the human intestinal tract. The E. coli cell (Fig. 1-5a) is an ovoid about 2 μm long and a little less than 1 μm in diameter, but other bacteria may be spherical or rod-shaped, and some are substantially larger. E. coli has a protective outer membrane and an inner plasma membrane that encloses the cytoplasm and the nucleoid. Between the inner and outer membranes is a thin but strong layer of a high molecular weight polymer (peptidoglycan) that gives the cell its shape and rigidity. The plasma membrane and the layers outside it constitute the cell envelope. The plasma membranes of bacteria consist of a thin bilayer of lipid molecules penetrated by proteins. Archaeal plasma membranes have a similar architecture, but the lipids can be strikingly different from those of bacteria (see Fig. 10-6).

FIGURE 1-5 Some common structural features of bacterial and archaeal cells. (a) This correct-scale drawing of E. coli serves to illustrate some common features. (b) The cell envelope of gram-positive bacteria is a single membrane with a thick, rigid layer of peptidoglycan on its outside surface. A variety of polysaccharides and other complex polymers are interwoven with the peptidoglycan, and surrounding the whole is a porous “solid layer” composed of glycoproteins. (c) E. coli is gram-negative and has a double membrane. Its outer membrane has a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on the outer surface and phospholipids on the inner surface. This outer membrane is studded with protein channels (porins) that allow small molecules, but not proteins, to diffuse through. The inner (plasma) membrane, made of phospholipids and proteins, is impermeable to both large and small molecules. Between the inner and outer membranes, in the periplasm, is a thin layer of peptidoglycan, which gives the cell shape and rigidity, but does not retain Gram’s stain. (d) Archaeal membranes vary in structure and composition, but all have a single membrane surrounded by an outer layer that includes either a peptidoglycan-like structure or a porous protein shell (solid layer), or both. [(a) David S. Goodsell. (b, c, d) Information from S.-V. Albers and B. H. Meyer, Nature Rev. Microbiol. 9:414, 2011, Fig. 2.]

Bacteria and archaea have group-specific specializations of their cell envelopes (Fig. 1-5b–d). Some bacteria, called gram-positive because they are colored by Gram’s stain (introduced by Hans Christian Gram in 1884), have a thick layer of peptidoglycan outside their plasma membrane but lack an outer membrane. Gram-negative bacteria have an outer membrane composed of a lipid bilayer into which are inserted complex lipopolysaccharides and proteins called porins that provide transmembrane channels for the diffusion of low molecular weight compounds and ions across this outer membrane. The structures outside the plasma membrane of archaea differ from organism to organism, but they, too, have a layer of peptidoglycan or protein that confers rigidity on their cell envelopes.

The cytoplasm of E. coli contains about 15,000 ribosomes, various numbers (from 10 to thousands) of copies of each of 1,000 or so different enzymes, perhaps 1,000 organic compounds of molecular weight less than 1,000 (metabolites and cofactors), and a variety of inorganic ions. The nucleoid contains a single, circular molecule of DNA, and the cytoplasm (like that of most bacteria) contains one or more smaller, circular segments of DNA called plasmids. In nature, some plasmids confer resistance to toxins and antibiotics in the environment. In the laboratory, these DNA segments are especially amenable to experimental manipulation and are powerful tools for genetic engineering (see Chapter 9).

Other species of bacteria, as well as archaea, contain a similar collection of biomolecules, but each species has physical and metabolic specializations related to its environmental niche and nutritional sources. Cyanobacteria, for example, have internal membranes specialized to trap energy from light (see Fig. 20-23). Many archaea live in extreme environments and have biochemical adaptations to survive in extremes of temperature, pressure, or salt concentration. Differences in ribosomal structure gave the first hints that Bacteria and Archaea constituted separate domains. Most bacteria (including E. coli) exist as individual cells, but often associate in biofilms or mats, in which large numbers of cells adhere to each other and to some solid substrate beneath or at an aqueous surface. Cells of some bacterial species (the myxobacteria, for example) show simple social behavior, forming many-celled aggregates in response to signals between neighboring cells.

Eukaryotic Cells Have a Variety of Membranous Organelles, Which Can Be Isolated for Study

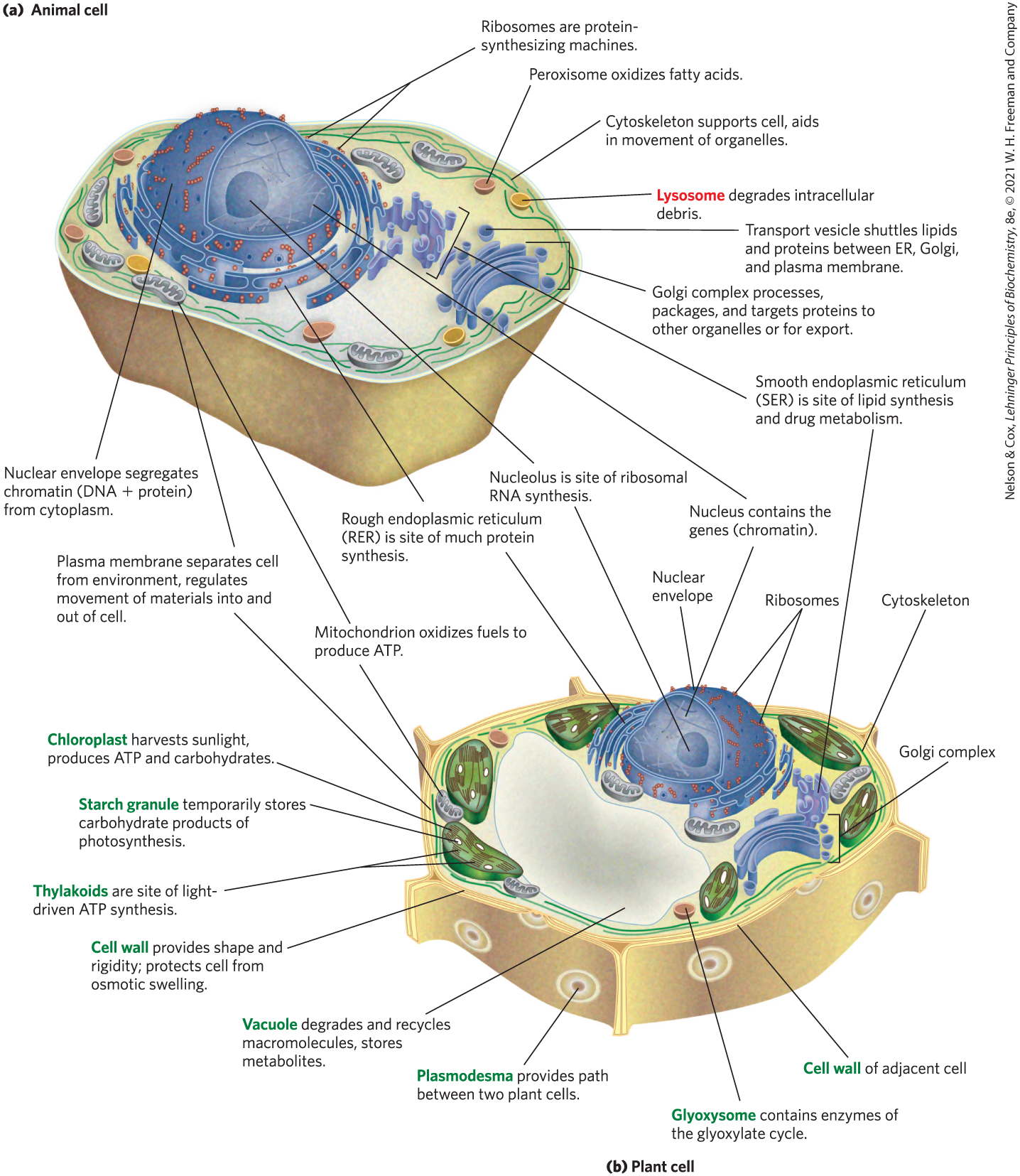

Typical eukaryotic cells (Fig. 1-6) are much larger than bacteria — commonly 5 to 100 μm in diameter, with cell volumes a thousand to a million times larger than those of bacteria. The distinguishing characteristics of eukaryotes are the nucleus and a variety of membrane-enclosed organelles with specific functions. These organelles include mitochondria, the site of most of the energy-extracting reactions of the cell; the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complexes, which play central roles in the synthesis and processing of lipids and membrane proteins; peroxisomes, in which very-long-chain fatty acids are oxidized and reactive oxygen species are detoxified; and lysosomes, filled with digestive enzymes to degrade unneeded cellular debris. In addition to these, plant cells contain vacuoles (which store large quantities of organic acids) and chloroplasts (in which sunlight drives the synthesis of ATP (adenosine triphosphate) in the process of photosynthesis). Also present in the cytoplasm of many cells are granules or droplets containing stored nutrients such as starch and fat.

FIGURE 1-6 Eukaryotic cell structure. Schematic illustrations of two major types of eukaryotic cell: (a) a representative animal cell and (b) a representative plant cell. Plant cells are usually 10 to 100 μm in diameter — larger than animal cells, which typically range from 5 to 30 μm Structures labeled in red are unique to animal cells; those labeled in green are unique to plant cells. Eukaryotic microorganisms (such as protists and fungi) have structures similar to those in plant and animal cells, but many also contain specialized organelles not illustrated here.

In a major advance in biochemistry, Albert Claude, Christian de Duve, and George Palade developed methods for separating organelles from the cytosol and from each other — an essential step in investigating their structures and functions. In a typical cell fractionation (Fig. 1-7), cells or tissues in solution are gently disrupted by physical shear. This treatment ruptures the plasma membrane but leaves most of the organelles intact. The homogenate is then centrifuged; organelles such as nuclei, mitochondria, and lysosomes differ in size and therefore sediment at different rates.

FIGURE 1-7 Subcellular fractionation of tissue. A tissue such as liver is first mechanically homogenized to break cells and disperse their contents in an aqueous buffer. The sucrose medium has an osmotic pressure similar to that in organelles, thus balancing diffusion of water into and out of the organelles, which would swell and burst in a solution of lower osmolarity (see Fig. 2-12). The large and small particles in the suspension can be separated by centrifugation at different speeds. Larger particles sediment more rapidly than small particles, and soluble material does not sediment. By careful choice of the conditions of centrifugation, subcellular fractions can be separated for biochemical characterization. [Information from B. Alberts et al., Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2nd edn, p. 165, Garland Publishing, 1989.]

These methods were used to establish, for example, that lysosomes contain degradative enzymes, mitochondria contain oxidative enzymes, and chloroplasts contain photosynthetic pigments. The isolation of an organelle enriched in a certain enzyme is often the first step in the purification of that enzyme.

The Cytoplasm Is Organized by the Cytoskeleton and Is Highly Dynamic

Fluorescence microscopy reveals several types of protein filaments crisscrossing the eukaryotic cell, forming an interlocking three-dimensional meshwork, the cytoskeleton. Eukaryotes have three general types of cytoplasmic filaments — actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments (Fig. 1-8) — differing in width (from about 6 nm to 22 nm), composition, and specific function. All types provide structure and organization to the cytoplasm and shape to the cell. Actin filaments and microtubules also help to produce the motion of organelles or of the whole cell.

FIGURE 1-8 The three types of cytoskeletal filaments: actin filaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments. Cellular structures can be labeled with an antibody (that recognizes a characteristic protein) covalently attached to a fluorescent compound. The stained structures are visible when the cell is viewed with a fluorescence microscope. (a) In this cultured fibroblast cell, bundles of actin filaments are stained red; microtubules, radiating from the cell center, are stained green; and chromosomes (in the nucleus) are stained blue. (b) A newt lung cell undergoing mitosis. Microtubules (green), attached to structures called kinetochores (yellow) on the condensed chromosomes (blue), pull the chromosomes to opposite poles, or centrosomes (magenta), of the cell. Intermediate filaments, made of keratin (red), maintain the structure of the cell.

Each type of cytoskeletal component consists of simple protein subunits that associate noncovalently to form filaments of uniform thickness. These filaments are not permanent structures; they undergo constant disassembly into their protein subunits and reassembly into filaments. Their locations in cells are not rigidly fixed but may change dramatically with mitosis, cytokinesis, amoeboid motion, or other changes in cell shape. The assembly, disassembly, and location of all types of filaments are regulated by other proteins, which serve to link or bundle the filaments or to move cytoplasmic organelles along the filaments. (Bacteria contain actinlike proteins that serve similar roles in those cells.)

The filaments disassemble and then reassemble elsewhere. Membranous vesicles bud from one organelle and fuse with another. Organelles move through the cytoplasm along protein filaments, their motion powered by energy-dependent motor proteins. The endomembrane system (see Fig. 11-4) segregates specific metabolic processes and provides surfaces on which certain enzyme-catalyzed reactions occur. Exocytosis and endocytosis, mechanisms of transport (out of and into cells, respectively) that involve membrane fusion and fission, provide paths between the cytoplasm and the surrounding medium, allowing the secretion of substances produced in the cell and uptake of extracellular materials.

This structural organization of the cytoplasm is far from random. The motion and positioning of organelles and cytoskeletal elements are under tight regulation, and at certain stages in its life, a eukaryotic cell undergoes dramatic, finely orchestrated reorganizations, such as the events of mitosis. The interactions between the cytoskeleton and organelles are noncovalent, reversible, and subject to regulation in response to various intracellular and extracellular signals.

Cells Build Supramolecular Structures

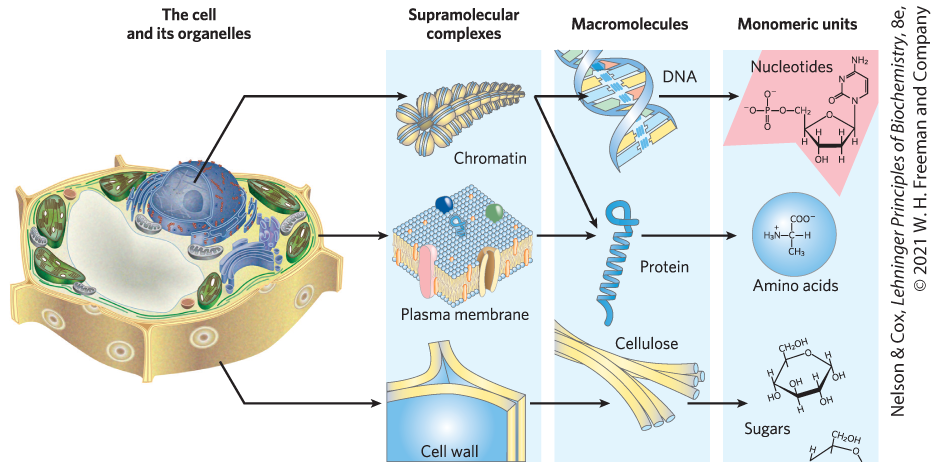

Macromolecules and their monomeric subunits differ greatly in size. An alanine molecule is less than 0.5 nm long. A molecule of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein of erythrocytes (red blood cells), consists of nearly 600 amino acid subunits in four long chains, folded into globular shapes and associated in a structure 5.5 nm in diameter. In turn, proteins are much smaller than ribosomes (about 20 nm in diameter), which are much smaller than organelles such as mitochondria, typically 1 μm in diameter. It is a long jump from simple biomolecules to cellular structures that can be seen with the light microscope. Figure 1-9 illustrates the structural hierarchy in cellular organization.

FIGURE 1-9 Structural hierarchy in the molecular organization of cells. The organelles and other relatively large components of cells are composed of supramolecular complexes, which in turn are composed of smaller macromolecules and even smaller molecular subunits. For example, the nucleus of this plant cell contains chromatin, a supramolecular complex that consists of DNA and basic proteins (histones). DNA is made up of simple monomeric subunits (nucleotides), as are proteins (amino acids). [Information from W. M. Becker and D. W. Deamer, The World of the Cell, 2nd edn, Fig. 2-15, Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, 1991.]

The monomeric subunits of proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides are joined by covalent bonds. In supramolecular complexes, however, macromolecules are held together largely by noncovalent interactions — much weaker, individually, than covalent bonds. Among these noncovalent interactions are hydrogen bonds; ionic interactions (between charged groups); and aggregations of nonpolar groups in aqueous solution, brought about by van der Waals interactions (also called London forces) and by the hydrophobic effect — all of which have energies much smaller than those of covalent bonds. (These noncovalent interactions are described in Chapter 2.) The large numbers of weak interactions between macromolecules in supramolecular complexes stabilize these assemblies, producing their unique structures.

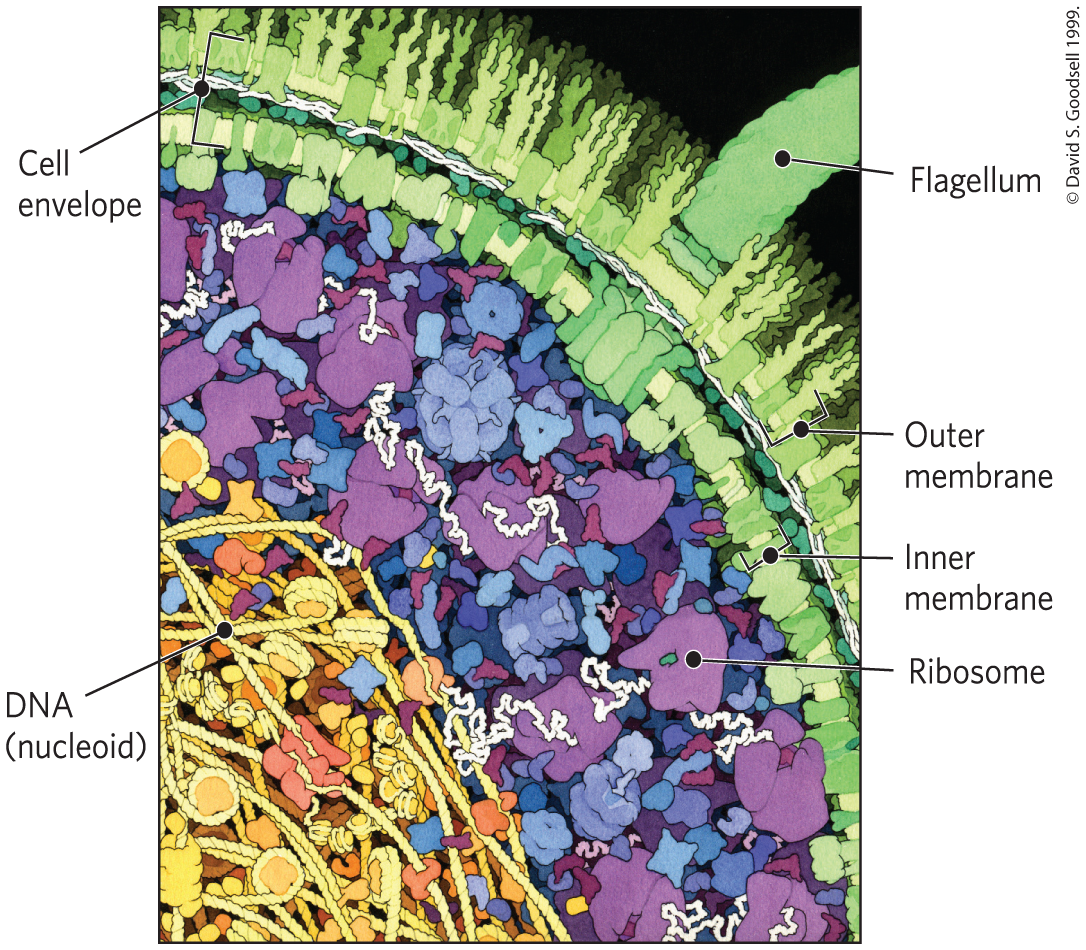

In Vitro Studies May Overlook Important Interactions among Molecules

One approach to understanding a biological process is to study purified molecules in vitro (from the Latin, meaning “in glass” — in the test tube), without interference from other molecules present in the intact cell — that is, in vivo (from the Latin, meaning “in the living”). Although this approach has been remarkably revealing, we must keep in mind that the inside of a cell is quite different from the inside of a test tube. The “interfering” components eliminated by purification may be critical to the biological function or regulation of the molecule that is being purified. For example, in vitro studies of pure enzymes are commonly done at very low enzyme concentrations in thoroughly stirred aqueous solutions. In the cell, an enzyme is dissolved or suspended in the gel-like cytosol with thousands of other proteins, some of which bind to that enzyme and influence its activity. Some enzymes are components of multienzyme complexes in which reactants are channeled from one enzyme to another, never entering the bulk solvent. When all of the known macromolecules in a cell are represented in their known dimensions and concentrations (Fig. 1-10), it is clear that the cytosol is very crowded and that diffusion of macromolecules within the cytosol must be slowed by collisions with other large structures. In short, a given molecule may behave quite differently in the cell than it behaves in vitro. A central challenge of biochemistry is to understand the influences of cellular organization and macromolecular associations on the function of individual enzymes and other biomolecules — to understand function in vivo as well as in vitro.

FIGURE 1-10 The crowded cell. This drawing is an accurate representation of the relative sizes and numbers of macromolecules in one small region of an E. coli cell.

SUMMARY 1.1 Cellular Foundations

- All cells share certain fundamental properties: they are bounded by a plasma membrane; have a cytosol containing metabolites, coenzymes, inorganic ions, and enzymes; and have a set of genes contained within a nucleoid (bacteria and archaea) or a nucleus (eukaryotes).

- The size of cells is limited by the need to deliver oxygen to all parts of the cell.

- By comparing their DNA sequences, researchers can place organisms in three domains: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. Archaea and Eukarya are more closely related to each other than either is to Bacteria.

- All organisms require a source of energy to perform cellular work. Phototrophs obtain energy from sunlight; chemotrophs obtain energy from chemical fuels.

- Bacterial and archaeal cells contain cytosol, a nucleoid, and plasmids, all within a cell envelope.

- Eukaryotes contain a nucleus and a variety of membrane-enclosed organelles with specialized function, which can be studied in the isolated organelles.

- Cytoskeletal proteins assemble into long filaments that give cells shape and rigidity and serve as rails along which cellular organelles move throughout the cell. The membrane-bounded compartments constitute an interconnected and dynamic endomembrane system.

- Supramolecular complexes held together by noncovalent interactions are part of a hierarchy of structures, some visible with the light microscope.

- Studying isolated cellular components in vitro simplifies the experimental system, but such study may overlook important interactions that occur in the living cell.

Despite these obvious differences, all cells of the simplest and most complex organisms share certain fundamental properties, which can be seen at the biochemical level.

Despite these obvious differences, all cells of the simplest and most complex organisms share certain fundamental properties, which can be seen at the biochemical level. We can classify organisms according to how they obtain the energy and carbon they need for synthesizing cellular material (as summarized in

We can classify organisms according to how they obtain the energy and carbon they need for synthesizing cellular material (as summarized in  The cytoplasm of E. coli contains about 15,000 ribosomes, various numbers (from 10 to thousands) of copies of each of 1,000 or so different enzymes, perhaps 1,000 organic compounds of molecular weight less than 1,000 (metabolites and cofactors), and a variety of inorganic ions. The nucleoid contains a single, circular molecule of DNA, and the cytoplasm (like that of most bacteria) contains one or more smaller, circular segments of DNA called plasmids. In nature, some plasmids confer resistance to toxins and antibiotics in the environment. In the laboratory, these DNA segments are especially amenable to experimental manipulation and are powerful tools for genetic engineering (see

The cytoplasm of E. coli contains about 15,000 ribosomes, various numbers (from 10 to thousands) of copies of each of 1,000 or so different enzymes, perhaps 1,000 organic compounds of molecular weight less than 1,000 (metabolites and cofactors), and a variety of inorganic ions. The nucleoid contains a single, circular molecule of DNA, and the cytoplasm (like that of most bacteria) contains one or more smaller, circular segments of DNA called plasmids. In nature, some plasmids confer resistance to toxins and antibiotics in the environment. In the laboratory, these DNA segments are especially amenable to experimental manipulation and are powerful tools for genetic engineering (see  All cells share certain fundamental properties: they are bounded by a plasma membrane; have a cytosol containing metabolites, coenzymes, inorganic ions, and enzymes; and have a set of genes contained within a nucleoid (bacteria and archaea) or a nucleus (eukaryotes).

All cells share certain fundamental properties: they are bounded by a plasma membrane; have a cytosol containing metabolites, coenzymes, inorganic ions, and enzymes; and have a set of genes contained within a nucleoid (bacteria and archaea) or a nucleus (eukaryotes).