Part I STRUCTURE AND CATALYSIS

Biochemistry uses the techniques and insights of chemistry to understand the amazing properties and activities of living organisms. This requires at the outset that the student acquire the vocabulary and language of biochemistry, which are provided in Part I.

The chapters of Part I are devoted to the structure and function of the major classes of cellular constituents: water (Chapter 2), amino acids and proteins (Chapters 3 through 6), sugars and polysaccharides (Chapter 7), nucleotides and nucleic acids (Chapter 8), fatty acids and lipids (Chapter 10), and, finally, membranes and membrane signaling proteins (Chapters 11 and 12). We also discuss, in the context of structure and function, the technologies used to study each class of biomolecules. One whole chapter (Chapter 9) is devoted entirely to biotechnologies associated with cloning and genomics.

We begin, in Chapter 2, with water, because its properties affect the structure and function of all other cellular constituents. For each class of organic molecules, we first consider the covalent chemistry of the monomeric units (amino acids, monosaccharides, nucleotides, and fatty acids) and then describe the structure of the macromolecules and supramolecular complexes derived from them. An overarching theme is that the polymeric macromolecules in living systems, though large, are highly ordered chemical entities, with specific sequences of monomeric subunits giving rise to discrete structures and functions. This fundamental theme can be broken down into three interrelated principles: (1) the unique structure of each macromolecule determines its function; (2) noncovalent interactions play a critical role in the structure and thus the function of macromolecules; and (3) the monomeric subunits in polymeric macromolecules occur in specific sequences, representing a form of information on which the ordered living state depends.

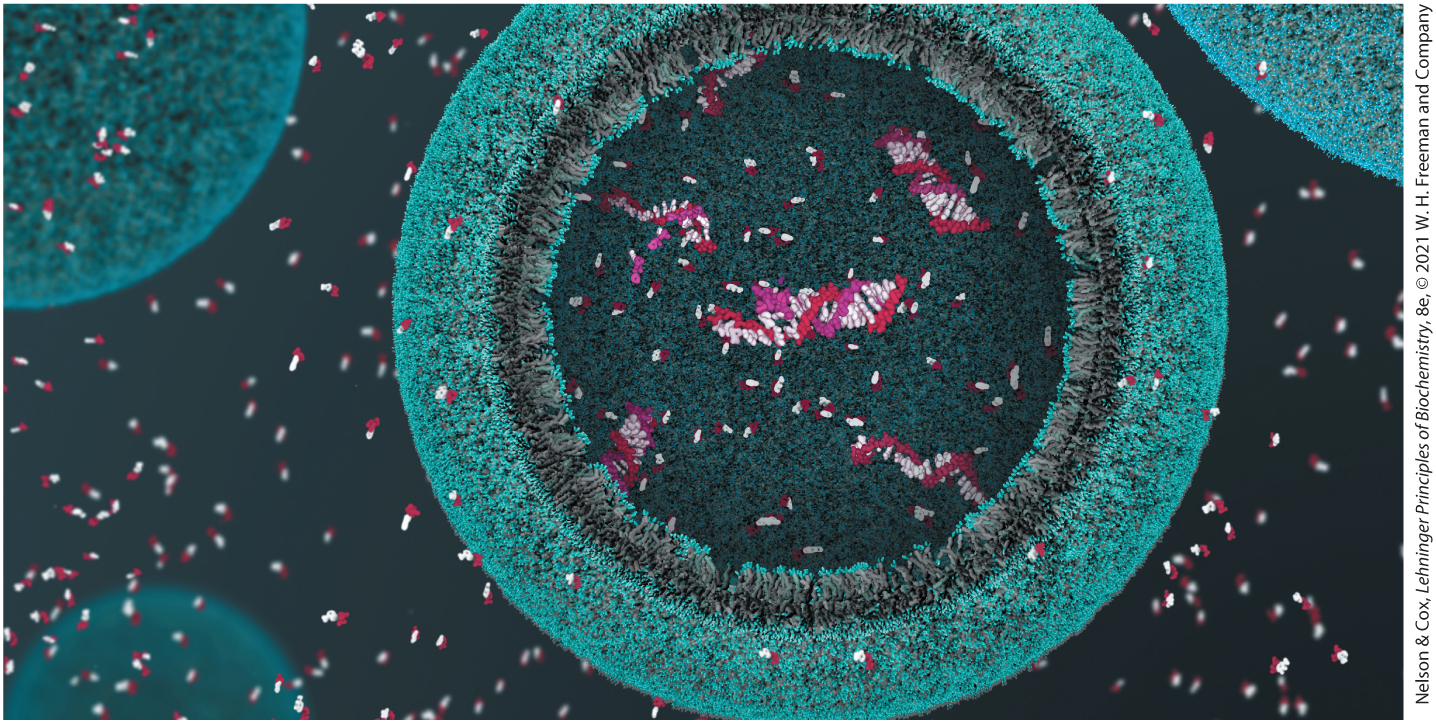

The relationship between structure and function is especially evident in proteins, which exhibit an extraordinary diversity of functions. One particular polymeric sequence of amino acids produces a strong, fibrous structure found in hair and wool; another produces a protein that transports oxygen in the blood; a third binds other proteins and catalyzes cleavage of the bonds between their amino acids. Similarly, the special functions of polysaccharides, nucleic acids, and lipids can be understood as resulting directly from their chemical structure, with their characteristic monomeric subunits precisely linked to form functional polymers. Sugars linked together become energy stores, structural fibers, and points of specific molecular recognition; nucleotides strung together in DNA or RNA provide the blueprint for an entire organism; and aggregated lipids form membranes. Chapter 12 unifies the discussion of biomolecule function, describing how specific signaling systems regulate the activities of biomolecules—within a cell, within an organ, and among organs—to keep an organism in homeostasis. Failure to maintain homeostasis results in failed function—that is, disease.

As we move from monomeric units to larger and larger polymers, the chemical focus shifts from covalent bonds to noncovalent interactions. Covalent bonds, at the monomeric and macromolecular level, place constraints on the shapes assumed by large biomolecules. It is the numerous noncovalent interactions, however, that dictate the stable, native conformations of large molecules while permitting the flexibility necessary for their biological function. As we shall see, noncovalent interactions are essential to the catalytic power of enzymes, the critical interaction of complementary base pairs in nucleic acids, and the arrangement and properties of lipids in membranes. The principle that sequences of monomeric subunits are rich in information emerges most fully in the discussion of nucleic acids (Chapter 8). However, proteins and some short polymers of sugars (oligosaccharides) are also information-rich molecules. The amino acid sequence is a form of information that directs the folding of the protein into its unique three-dimensional structure and ultimately determines the function of the protein. Some oligosaccharides also have unique sequences and three-dimensional structures that are recognized by other macromolecules.

Each class of molecules has a similar structural hierarchy: subunits of fixed structure are connected by bonds of limited flexibility to form macromolecules with three-dimensional structures determined by noncovalent interactions. These macromolecules then interact to form the supramolecular structures and organelles that allow a cell to carry out its many metabolic functions. Together, the molecules described in Part I are the stuff of life.