Chapter 11 BIOLOGICAL MEMBRANES AND TRANSPORT

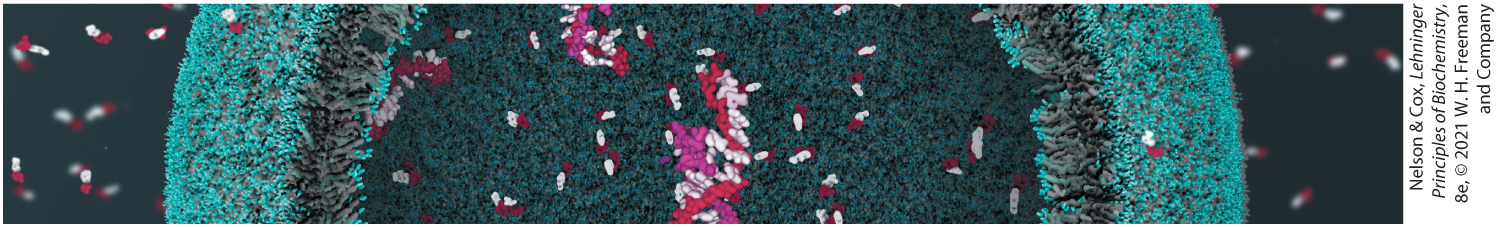

The first cell probably came into being when a membrane formed, enclosing a small volume of aqueous solution and separating it from the rest of the universe. Membranes define the external boundaries of cells and control the molecular traffic across that boundary; in eukaryotic cells, they also divide the internal space into discrete compartments to segregate processes and components. Proteins embedded in and associated with membranes organize complex reaction sequences and are central to both biological energy conservation and cell-to-cell communication.

In this chapter we focus on these principles that underlie the structure and function of biological membranes:

The biological membrane is a lipid bilayer with proteins of various functions (enzymes, transporters) embedded in or associated with the bilayer. The hydrophobic effect stabilizes structures (lipid bilayers and vesicles) in which lipids with some polar and some nonpolar regions can protect their nonpolar regions from interaction with the very polar solvent, water. Membrane proteins are associated with the lipid bilayer more-or-less tightly, and proteins and lipids are both allowed limited lateral motion in the plane of the bilayer.

All of the internal membranes of cells are part of an interconnected, functionally specialized, and dynamic endomembrane system. Proteins and lipids synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum move through the Golgi apparatus, and they are targeted to the membranes of organelles or to the plasma membrane, where they provide the essential properties of these structures. During this membrane trafficking, some proteins are covalently altered, and some lipids are segregated into different organelles or are concentrated in one of the bilayer leaflets. Rafts are functionally specialized regions with unique lipid and protein compositions.

Although the lipid bilayer is impermeable to charged or polar solutes, cells of all kinds have many membrane transporters and ion channels that catalyze transmembrane movement of specific solutes. Some transporters merely speed the movement of solutes in the direction that simple diffusion takes them, whereas others use an energy source to move solutes against a concentration gradient.

The biological membrane is a lipid bilayer with proteins of various functions (enzymes, transporters) embedded in or associated with the bilayer. The hydrophobic effect stabilizes structures (lipid bilayers and vesicles) in which lipids with some polar and some nonpolar regions can protect their nonpolar regions from interaction with the very polar solvent, water. Membrane proteins are associated with the lipid bilayer more-or-less tightly, and proteins and lipids are both allowed limited lateral motion in the plane of the bilayer.

The biological membrane is a lipid bilayer with proteins of various functions (enzymes, transporters) embedded in or associated with the bilayer. The hydrophobic effect stabilizes structures (lipid bilayers and vesicles) in which lipids with some polar and some nonpolar regions can protect their nonpolar regions from interaction with the very polar solvent, water. Membrane proteins are associated with the lipid bilayer more-or-less tightly, and proteins and lipids are both allowed limited lateral motion in the plane of the bilayer. All of the internal membranes of cells are part of an interconnected, functionally specialized, and dynamic endomembrane system. Proteins and lipids synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum move through the Golgi apparatus, and they are targeted to the membranes of organelles or to the plasma membrane, where they provide the essential properties of these structures. During this membrane trafficking, some proteins are covalently altered, and some lipids are segregated into different organelles or are concentrated in one of the bilayer leaflets. Rafts are functionally specialized regions with unique lipid and protein compositions.

All of the internal membranes of cells are part of an interconnected, functionally specialized, and dynamic endomembrane system. Proteins and lipids synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum move through the Golgi apparatus, and they are targeted to the membranes of organelles or to the plasma membrane, where they provide the essential properties of these structures. During this membrane trafficking, some proteins are covalently altered, and some lipids are segregated into different organelles or are concentrated in one of the bilayer leaflets. Rafts are functionally specialized regions with unique lipid and protein compositions. Although the lipid bilayer is impermeable to charged or polar solutes, cells of all kinds have many membrane transporters and ion channels that catalyze transmembrane movement of specific solutes. Some transporters merely speed the movement of solutes in the direction that simple diffusion takes them, whereas others use an energy source to move solutes against a concentration gradient.

Although the lipid bilayer is impermeable to charged or polar solutes, cells of all kinds have many membrane transporters and ion channels that catalyze transmembrane movement of specific solutes. Some transporters merely speed the movement of solutes in the direction that simple diffusion takes them, whereas others use an energy source to move solutes against a concentration gradient.